Security research in the age of AI tools: Django and Node.js SQL injection analysis

In this article, I try to show how my work as a security researcher has changed and how the new AI tools have impacted my workflow, productivity, and overall approach to security research. I present two SQL injection vulnerabilities discovered by other researchers, show how I investigated them to create security checks for our Invicti DAST product, and describe how AI tools helped me in the process.

Vulnerability 1: Critical SQL Injection Vulnerability in Django (CVE-2025-64459)

The first vulnerability was published by Endor Labs (by Meenakshi S L) in their blog post Critical SQL Injection Vulnerability in Django (CVE-2025-64459). This vulnerability is particularly interesting because it affects a widely used web framework, Django.

Step 1: Get a broad idea of the vulnerability

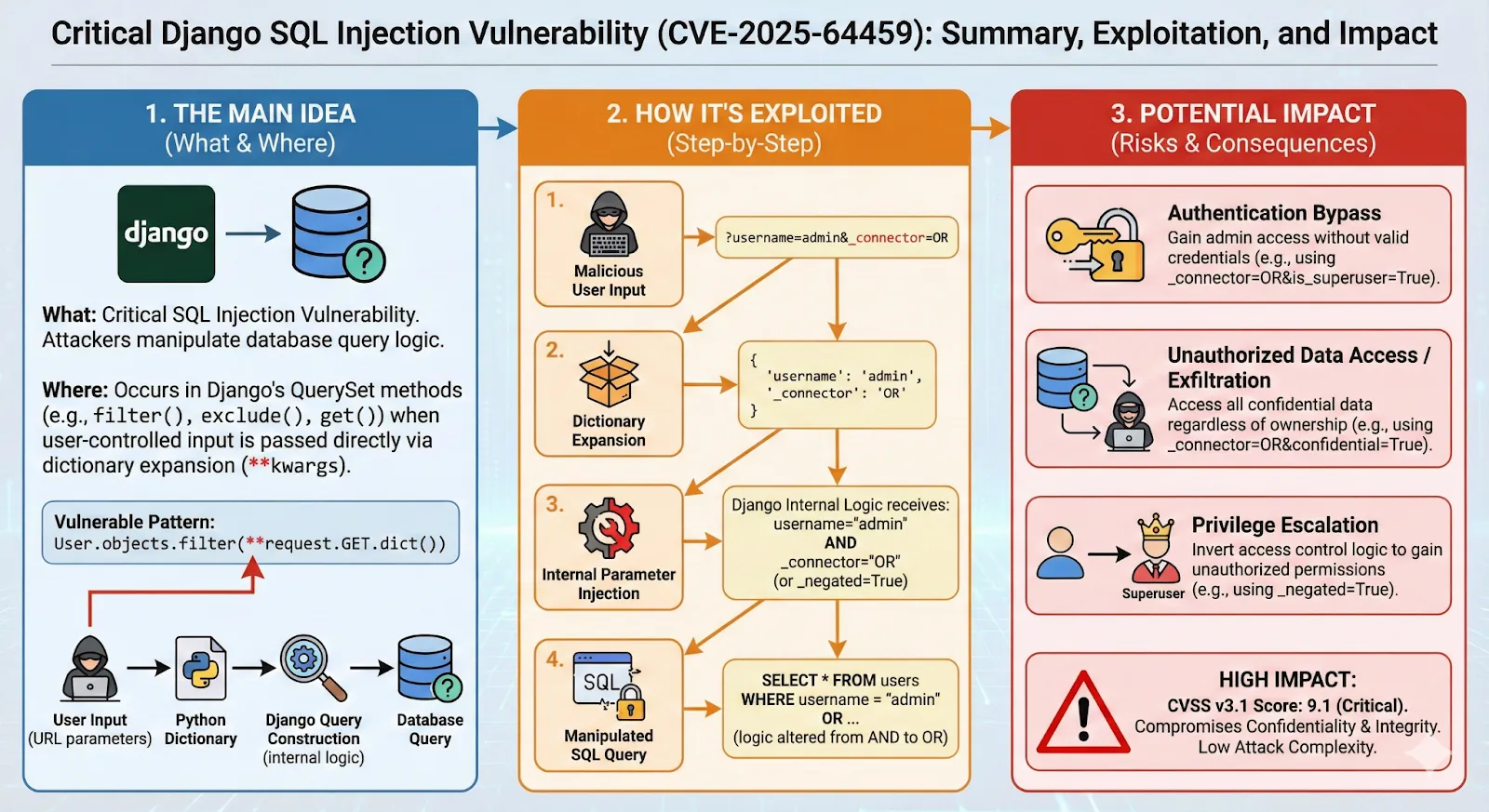

Since Google released the image model Nano Banana Pro, I’ve learned that it can also be used to summarize text and create infographics that make understanding complex topics faster/easier. So, I used Nano Banana Pro to generate an infographic summarizing the vulnerability from the blog post text.

I used the following prompt:

It generated the following infographic:

It’s a great way to get a quick overview of the vulnerability and its impact. However, I still needed to understand the technical details, so of course I read the full blog post as well, but the infographic helped me to get a broad idea quickly and to understand the key points.

The main issue is that a very common dynamic filtering pattern in Django using user-controlled query parameters can lead to SQL injection. So, if you have code like this:

an attacker can exploit it using a query string like:

Django converts it into the following unsafe SQL query because of the internal _connector parameter:

Step 2: Reproduce the vulnerability with Claude Code

This step is where I was spending most of my time before I had all the AI tools. I had to set up a Django environment, create a vulnerable application, and then try to exploit it manually. All these steps took a lot of time, especially if I didn’t have prior experience with a specific application like Django.

Nowadays, I just use Claude Code to help me with this. In this case, I created an empty folder and asked Claude Code to generate a vulnerable Django application that demonstrates the vulnerability. I used the following prompt:

A few minutes later, I had a complete Django application with the vulnerable code and instructions on how to run it. I then asked Claude Code to generate a docker container for the application so I can run it easily without worrying about dependencies.

In the end, it generated a Dockerfile and a docker-compose.yml file for me. I just had to run docker-compose up and the vulnerable application was up and running.

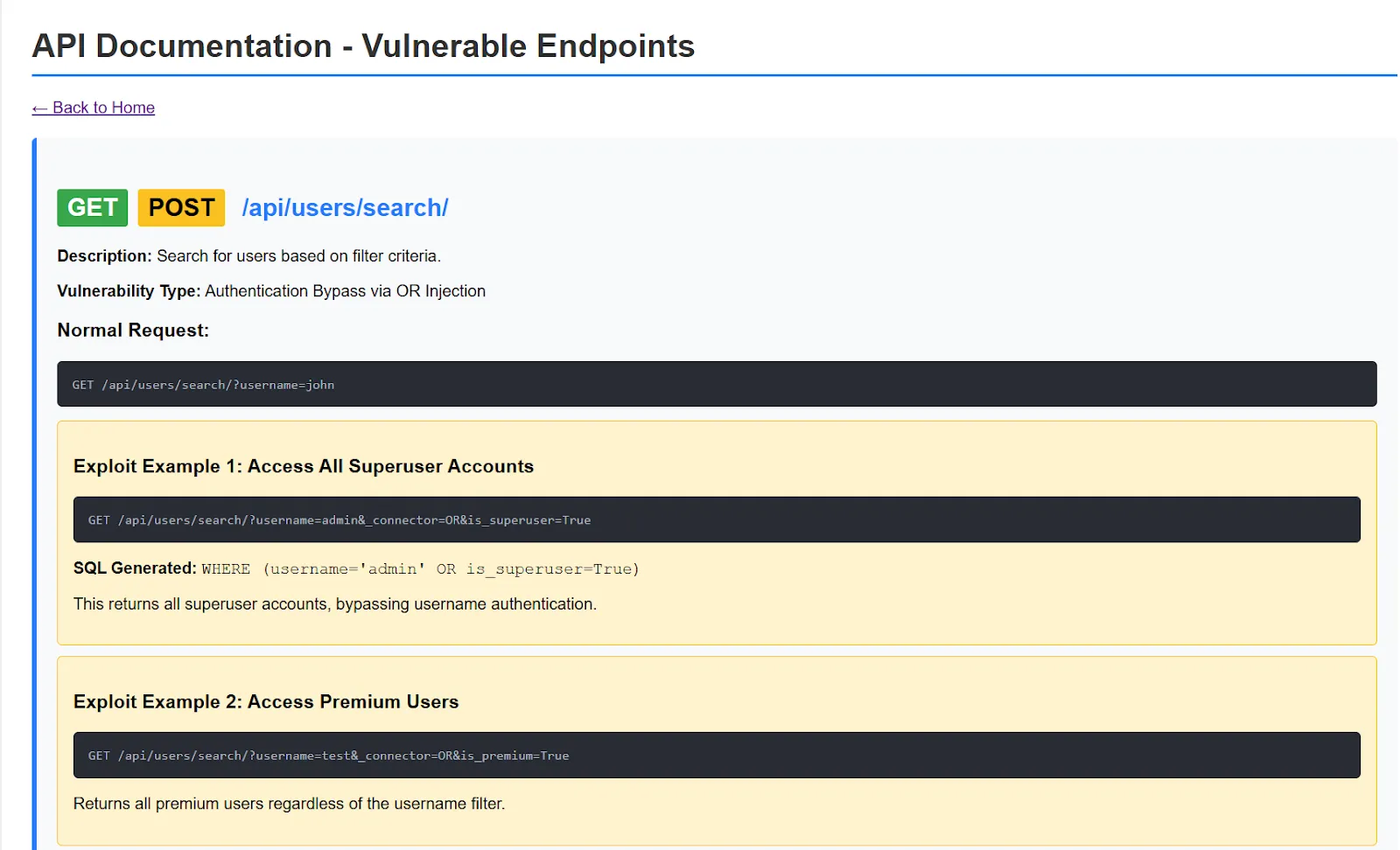

It also generated API documentation for the vulnerable endpoints so I can test them easily:

Step 3: Brainstorming the security check implementation with Claude Code

Now that I had a vulnerable application to test against, the next step was to figure out how to implement a security check for this vulnerability in our Invicti DAST product. The problem was that I needed to find a way to detect this vulnerability generically in Django applications. In the examples above, you need to know about the is_superuser field from the User model. I wanted to find a way to detect this vulnerability without prior knowledge of the models used in the application.

I asked Claude to help me brainstorm ideas for implementing the security check in a generic way. This is very helpful because I’m not an expert in Django whereas Claude has a lot of knowledge about Django internals and best practices. I used the following prompt:

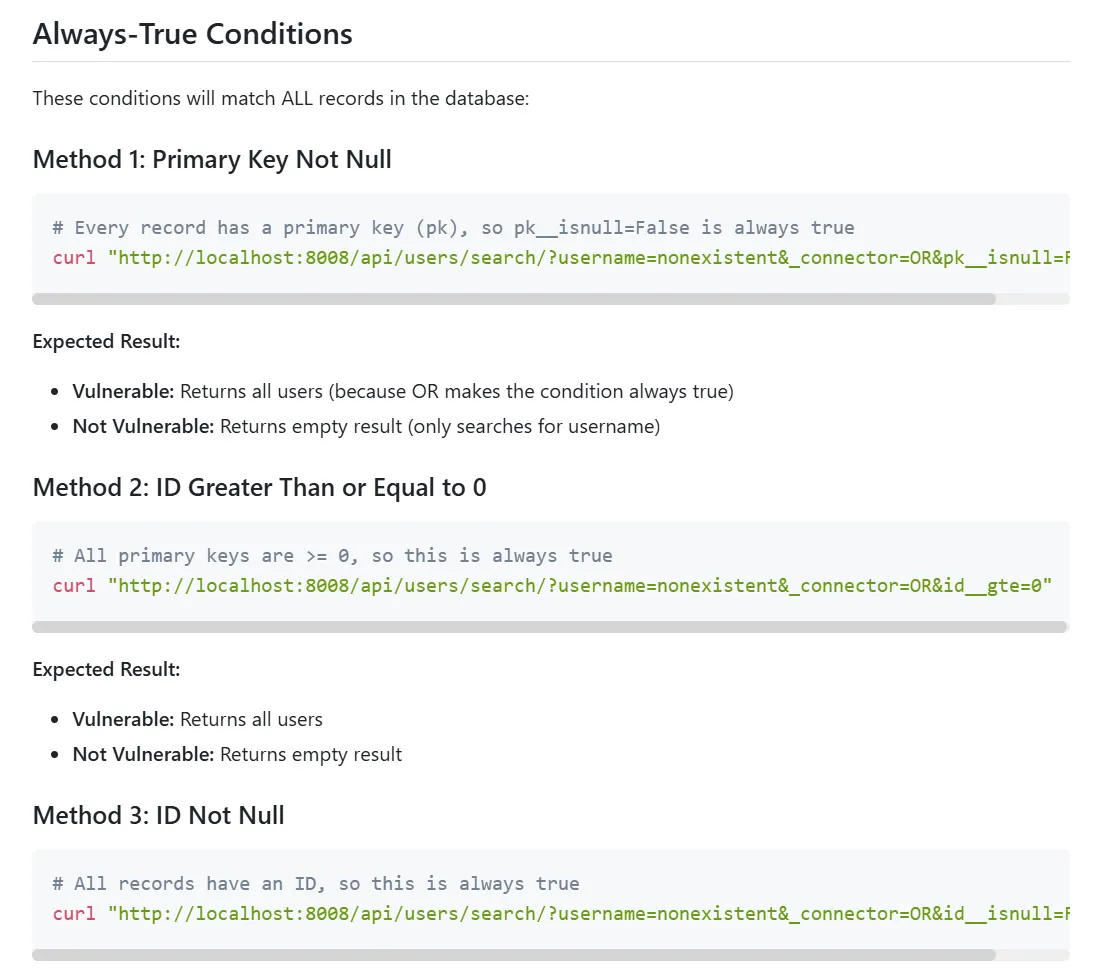

Claude Code suggested a few different approaches, and it even generated an HTML report with all the ideas and how they are supposed to work:

Of course, not all ideas you get from an LLM are always good and you should expect some hallucinations, but it gave me a good starting point to implement the security check. In the end, I used the id__gte=0 approach that results in a query string like ?username=nonexistent&_connector=OR&id__gte=0. The resulting query is always true because id is always greater than or equal to 0.

Step 4: Implementing the security check with Claude Code

I also use Claude Code in the last step of the process: implementing the security check. I’ve provided Claude Code with a detailed CLAUDE.md file (a special file that Claude automatically pulls into context when starting a conversation) about how our Invicti security checks work. This helps me to implement security checks much faster and also to write unit tests for them.

As you can see, I used some type of AI model in every step of the process, from understanding the vulnerability to brainstorming ideas to implementing the security check itself.

Vulnerability 2: Prepared Statements? Prepared to Be Vulnerable

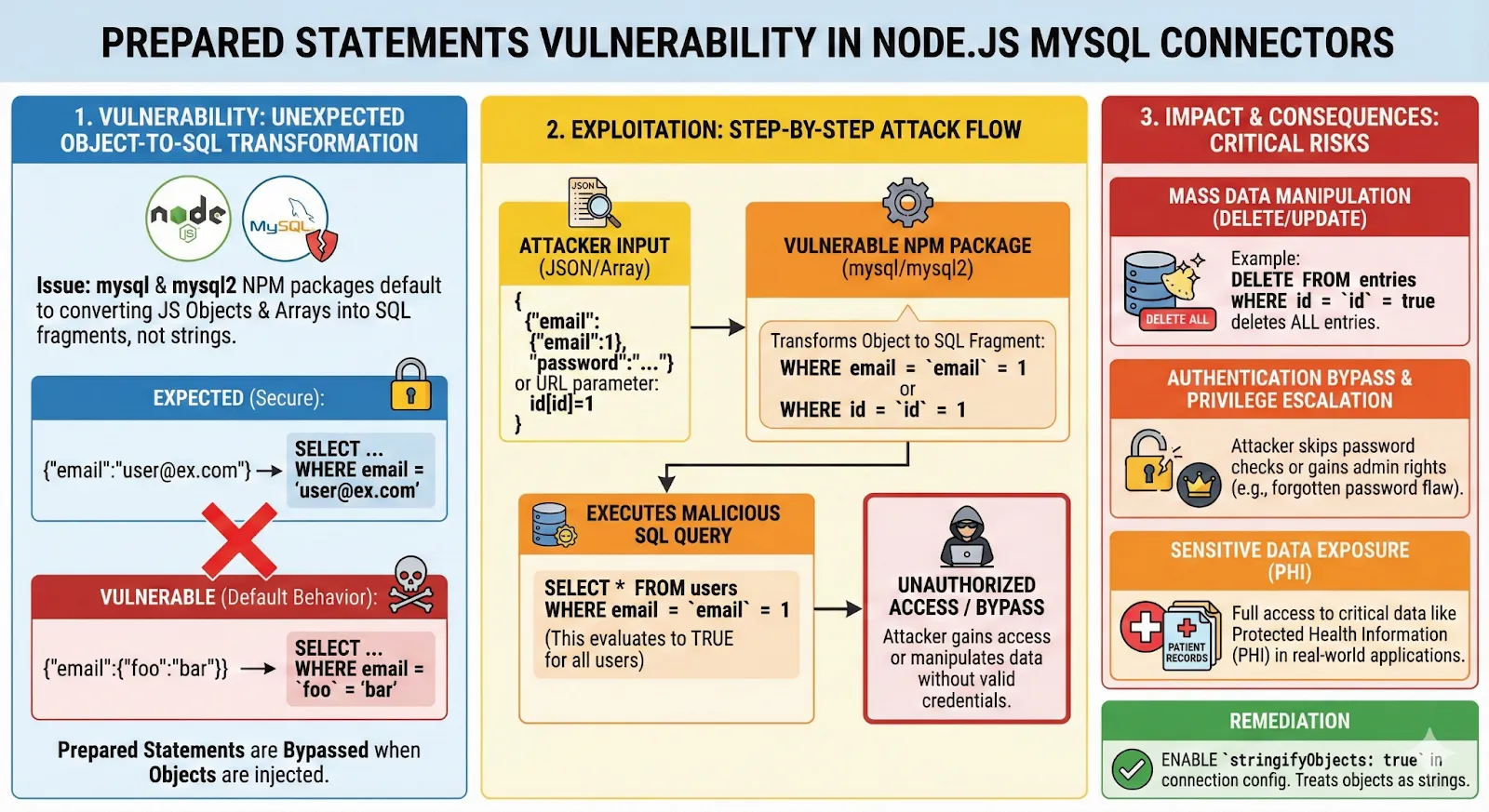

The second vulnerability was published by Mantra Infosec (by Balazs Bucsay) in their blog post Prepared Statements? Prepared to Be Vulnerable. This vulnerability highlights the risks associated with using prepared statements in Node.js web applications when combined with the mysql and mysql2 database connectors. Prepared statements are often considered a best practice for preventing SQL injection attacks, but Balazs shows how they can actually introduce vulnerabilities in the default configuration of this specific tech stack.

Step 1: Get a broad idea of the vulnerability

As before, I used Nano Banana Pro to generate an infographic summarizing the vulnerability from the blog post text. It generated the following infographic:

Again, it’s a great way to get a quick overview of the vulnerability and its impact.

The main issue is that when using prepared statements with the mysql and mysql2 connectors in Node.js, these drivers will by default turn JavaScript objects and arrays into raw SQL fragments. So if the code expects a plain string like test@example.com and you send a JSON object such as {"email": {"foo": "bar"}}, the connector rewrites the value into a tiny piece of SQL ('foo' = 'bar') and drops it into the prepared statement. An attacker can abuse this default behavior in multiple ways to perform SQL injection.

The fix is to use stringifyObjects: true in the connection configuration so that objects and arrays are safely converted to strings instead of SQL fragments.

Step 2: Reproduce the vulnerability with Claude Code

As before, I used Claude Code to generate a vulnerable Node.js application that demonstrates the vulnerability.

In an interesting twist, Claude Code generated two different connections strings, one with the vulnerable default configuration and one with the secure stringifyObjects: true configuration. The generated code looks like this:

It also generated two different endpoints, one using the vulnerable connection and one using the secure connection, so that I can test both configurations easily:

Step 3: Brainstorming the security check implementation with Claude Code

I reproduced the vulnerability easily. An expected URL looks like this:

http://127.0.0.1:3000/api/vulnerable/user?id=1

which will return the user with ID 1. You can exploit the vulnerability by sending a JSON object instead of a number as the id parameter:

http://127.0.0.1:3000/api/vulnerable/user?id[id]=1

This will return all users because the query becomes SELECT * FROM users WHERE id = 'id' = 1 which is always true.

This works well for number fields and I was curious to see if it works for string fields as well, and more specifically for GUID fields. So, I asked Claude Code to add an endpoint that uses a GUID field to see if the injection works there as well:

It adjusted the generated application to add a GUID field to the users table and created an endpoint that retrieves users by their GUID:

GET /api/vulnerable/user-by-guid?guid=550e8400-e29b-41d4-a716-446655440001

And of course, the injection worked perfectly:

GET /api/vulnerable/user-by-guid?guid[guid]=1

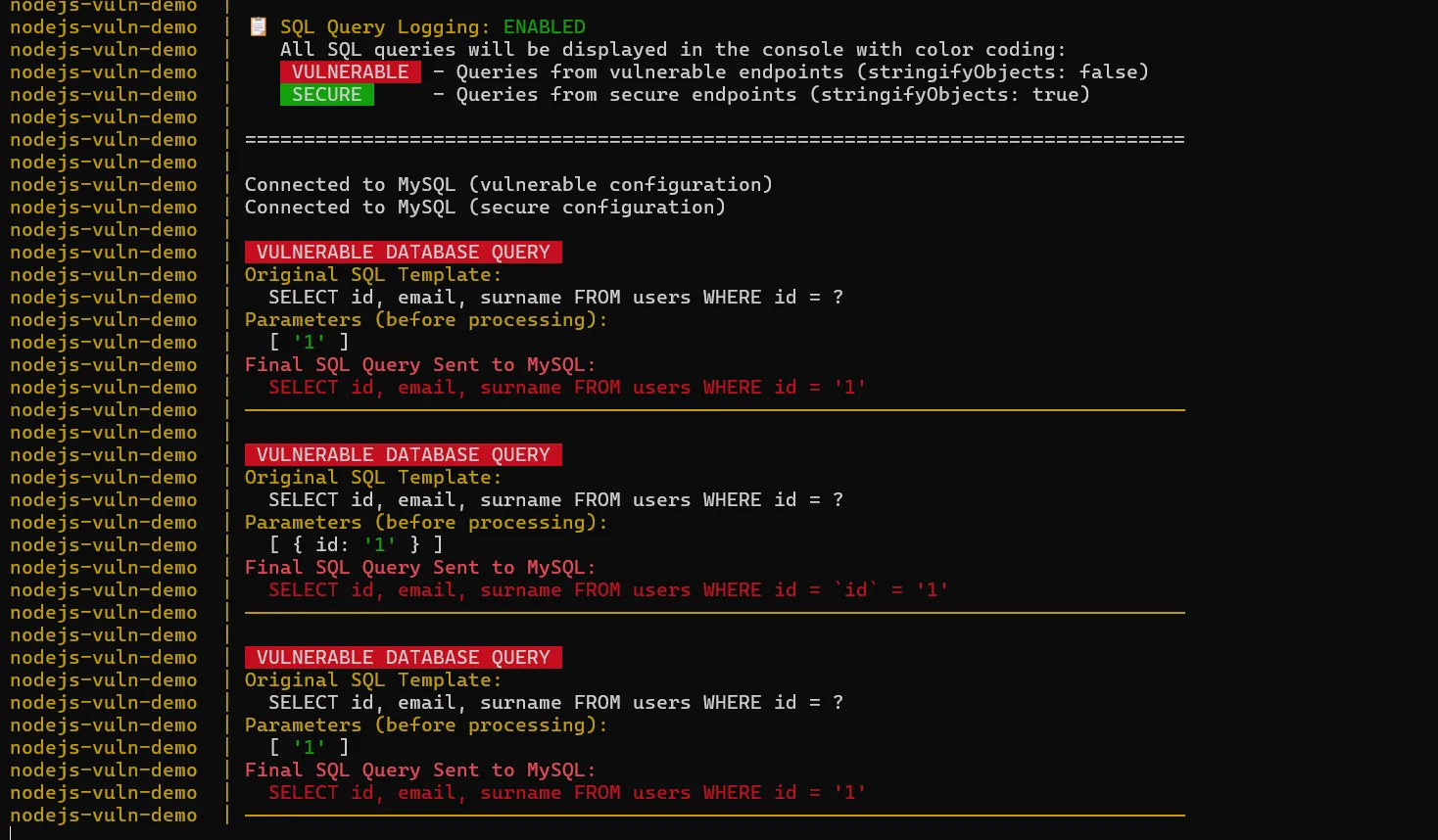

While investigating the vulnerability, I realized it would be helpful to see the SQL queries in the docker console to understand better how the injection works. So again, I asked Claude Code to help me modify the generated application to log all SQL queries to the console.

It generated for me this beautiful colorful SQL logger middleware that shows all queries executed by the application:

As you can imagine, this is very helpful for understanding how the injection works and for debugging the application.

Step 4: Implementing the security check with Claude Code

Having all the required knowledge about the vulnerability, I proceeded to implement the security check for this vulnerability in our Invicti DAST product using Claude Code, just like in the previous vulnerability.

Conclusion

I suspect that AI tools will become an important part of security research workflows in the near future. They can help with a wide variety of tasks, like helping to better understand vulnerabilities, creating vulnerable test environments, brainstorming ideas, and implementing security checks. As AI models continue to improve, I believe they will become even more useful for security researchers.