The Dark Web: Black Market Websites, Script Kiddies, Hacking and more…

Have you ever wondered about what happens in the digital black market, or as better known the dark web? Do you know how easy it is for someone who does not have any security experience to buy a tool that can find vulnerabilities in websites and exploit them automatically? Read this article for more detailed information of how the dark web evolved and about the things you and anyone else can do with just a little bit of money.

Your Information will be kept private.

Your Information will be kept private.

In this article, we explore the evolution of the digital black market. We first explore how the concept of currency evolved into a digital, anonymous form – a critical component of the modern vulnerabilities and illicit goods black market. Digital black markets have existed long prior to these anonymous, digital currencies – called cryptocurrencies due to using peer-to-peer encrypted and signed communications similar to BitTorrent – but those markets had existed for a long time much like their analogue predecessors, using cash or bank accounts. Those risks were mitigated with cryptocurrencies, but we explore how even the new, supposedly anonymous cryptocurrency solution is not without risk or incredible insecurity, either.

From there, we learn how digital black markets began pretty much with the beginnings of the Internet itself. Starting with, and for the longest time still existing on decades-old Internet technology, we explore the slow, progressive evolution on this platform. Systems like Bulletin Board Systems, Usenet, and later websites on the budding World Wide Web provided a home to these activities. We briefly explore why sellers (and buyers) take the risk, in spite of increased penalty and raids.

We continue to explore this "why" factor by examining one of these entities in person, discussing with the very people involved in these activities what their motives and agenda are. We find that a rebellious attitude, which we discuss in the prior section, largely drives these users, even knowing they face potentially decades in prison for their crimes if caught. From there, we discover how that attitude and new anonymizing technology solutions, namely TOR and Bitcoin, spawned a new, easy-to-use environment for even the everyday layman to purchase illicit goods. Physical and digital illicit goods have become as easily accessible and point-and-click as an Amazon purchase, and now this has yielded a new generation of the underground Internet ("dark web").

Finally, we explore how this almost social media-level of ease available on many dark web black market websites has resulted in a new genre: boutique exploits and software vulnerability trading. We learn how this has ultimately created a realm of computer attacks (e.g. Windows 0days) and website attacks (e.g. web scanning and exploiting packages) that anyone can use with just a simple understanding of TOR, Bitcoin, and a knowledge of how to use a Web 2.0-prettified website interface.

Introduction

The concept of time and the things that happen during its slow progression is utterly staggering. Did you know Cleopatra lived closer in time to the Moon landing than she did to the Great Pyramid of Giza being built in Cairo, Egypt? Here is another mind-blowing realization: The concept of currency trade for goods – cash, coin, crops, cattle, whatever people deem as valuable and worthy of trade – has existed for at least over twice as long as recorded history itself. It is estimated that recorded history began around 4,000 B.C., whereas currency in the form of bartering for goods has been around since at least 9,000 B.C., perhaps much longer.

For perhaps just as long, black markets have existed as well. While a market is an economic institution where tangible currency in some form is exchanged in trade for goods or services, a black market is similar, but involves either the currency exchange itself or the goods or services being traded being illegal. This is done typically to circumvent regulatory powers, avoid detection, or simply to obtain illicit or illegal goods.

With everything becoming more advanced and evolving into a digital format, the world now relies on the Internet and electronic currency to continue uninterrupted on its unfathomably rapid pace. Currency has seen its evolution from the bartering of grains and goats, to coins and promissory notes, to ones and zeros on a bustling stock exchange floor zooming by with millisecond trades. Black markets also participated in this evolution, and while some of the illicit goods have remain unchanged (such as drugs), many new ones have been borne of this evolution, such as software to take down websites and log peoples' keystrokes.

With the evolution of currency from commodity to fiat – that is, backed by tangible goods, like gold, to being valued solely by federated banking institutions, respectively – federation of currency itself has come under fire as an indefinably corruptible system. Through very recent advancements in technology and software, currency federation itself has started to become a thing of the past – a windfall digital black markets are more than happy to exploit.

Untraceable, Undetectable – Anonymous Currency

The great thing about cash is that aside from physical forensics (e.g. fingerprints, DNA, locality-specific trace elements, etc.), it is virtually untraceable. Barring any form of surveillance, it leaves no record of who spent it. You never see drug dealers on Breaking Bad use credit cards to buy illicit substances, because the transaction is traceable. Cash is king, as the saying goes, because unlike digitized transactions where everything can and will be logged, traced, and archived, cash grants that anonymity and a better guarantee of not getting caught. But cash is still physical.

Fast forward to today's era, and everything relies on digital currency instead of cash. Unlike some European countries, like Germany for instance, the United States and others rely heavily upon ethereal currency in the form of a 16-digit debit or credit card number in lieu of cash at every available opportunity. Governments like this because it grants explicit and traceable detail for an indefinite length of time; Black market merchants and customers despise it for those very same reasons. This has inspired the desire for an anonymous and decentralized currency. Many have been proposed, though almost all had floundered due to poor planning, implementation, or simply lack of widespread adoption. For the longest time, this was just a pipedream – until 2008 happened.

In 2008, an entity that went by the name of Satoshi Nakamoto (either a single person or team of people pretending to be one) released the Bitcoin payment system. Designed as a decentralized virtual cryptocurrency (a currency exchange of whole or fractional 'Bitcoins' using cryptography to ensure the security and integrity of transactions), the system utilizes an anonymous public ledger of hashed addresses of both wallets and the Bitcoins they possess. New Bitcoins are 'mined' and generated by doing complex computations spread across entire server farms, growing in complexity with each new Bitcoin (or BTC) generated. No names, addresses, or any information is known except for a historical record of what wallets have what Bitcoins (or slices of Bitcoins). The Bitcoin system itself also affords a level of peer-to-peer always-online security, being unable to succumb as easily to things like Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks – a fate PayPal experienced in 2010 when it chose to freeze Wikileaks' account. While this system affords quite an astoundingly high level of anonymity, it still has its risks of being traced to individual users.

Because it has no federated agency or nation-state backing its fiat value, nor any commodity to back it with tangible value, the trade equivalency of BTC-to-U.S. Dollar can fluctuate incredibly based purely on a commonly agreed-upon value between unofficial major monitoring and trading markets, or "Bitcoin exchanges." The value of BTC has fluctuated from a few cents to as high as $1,200 USD. These values, though, can change dramatically for any reason and at any time. When one of the largest modern digital black markets fell in 2013, the value of BTC plummeted 15% almost immediately. It recovered, but then when China banned their financial institutions from interacting with Bitcoins, the value dropped over 50%, by more than $500 USD. Extreme momentary fluctuations like "flash crashes" were known to happen occasionally, too, such as one case where the value went from $700 to $100 back to $655 in a single morning. Lately, the value of BTC has remained around on average $250 USD per BTC for all of 2015 thus far.

Bitcoin is also highly unstable in terms of fiduciary reliability. BTC are stored in a wallet.dat file which for the longest time was unencrypted on each person's local installation of the Bitcoin client. Steal someone's wallet.dat file and you possess any BTC associated to the Bitcoin addresses it holds. Various organizations, often the exchanges themselves, fell victim to this massive security flaw (one that went unrepaired for a surprisingly long time). AllCrypt, a smaller Bitcoin exchange, found itself victim to a SQL injection hack against its WordPress that compromised over $11,000 USD of BTC. Many others lost far more from wallet compromises – Bitcoinica losing $90,000 USD in 2012, Bitfloor losing over $250,000 USD later that year, Inputs.io losing over $1.3 million USD in 2013, most due to compromises of their websites via SQL injections or other web application vulnerabilities that typically can be identified automatically with an automated web application security scanner. The largest theft of all – over 850,000 BTC totaling $460 million USD – occurred against the Mt. Gox Bitcoin exchange for many reasons: website source code was not version controlled, all code changes bottlenecked with one person, and a myriad of long-unpatched website security flaws that allowed for the biggest BTC heist ever.

Even with the extreme instability of Bitcoin value and wallet security (eventually rectified), the anonymity it affords coupled with its widespread adoption has crowned it king of cryptocurrency. Others have spawned to try and take the throne, DogeCoin being among the most amusing (currently around $170 USD per 1 million Doge). Many different websites with a wide range of services and products now accept BTC and some derivative types, such as WordPress.com, Overstock.com, TigerDirect.com, even Tesla Motors. The argument has been made clear by users of the Internet (and real-world customers, too, with BTC gaining increased adoption in the brick-and-mortar market): anonymous cryptocurrency is here to stay – and indeed will be the currency of choice in digital black markets schemes. This all, however, raises an interesting question: if anonymous cryptocurrency came into popular usage only in 2008, how then did digital black markets exist for decades prior?

How Digital Black Markets Began – A Brief History

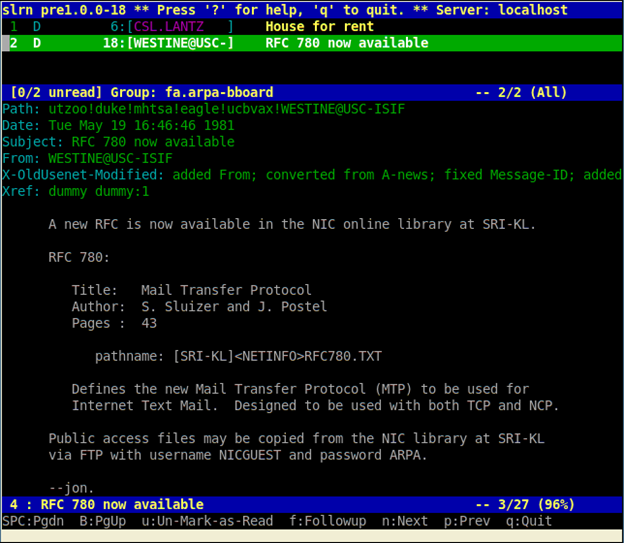

When everything in the world started the shift from analog to digital – or rather, from non-networked and offline to networked and online – so, too, did the idea of a black market. Originally, the concept began on systems like Usenet newsgroups. In the early days of the Internet, the world wide web did not yet exist, so people lucky enough to afford a 2,400 baud modem – the typical modem most users could enjoy for nearly 20 years – had to make due with simpler methods: email, bulletin board systems (BBS), and Usenet. Bulletin boards had some of these users, like the MindVox BBS and others, but Usenet groups are really where the concept flourished. The Usenet groups were often more difficult to find, too, which was a major reason for their popularity in this particular realm. Depending on the host – who were nowhere near as ubiquitous as they have been over the past decade – sometimes the content was heavily policed, but not always. With the proper newsreader client and server information, users could eventually find their way to these various shady Usenet groups that usually trafficked in illegal pornography, questionably legal electronics or software, and other items one would reasonably assume from such nefarious places, to perform their transactions.

Figure 1-Usenet newsgroup (Source: Newsgroup Reviews Blog)

Normally these markets employed less reliable exchange methods like physical trade, leaving cash at one drop point and retrieving the purchase elsewhere. This was not much different from the way some black market trading had existed for centuries. The only difference at that point was just a new medium of communication, so, in general, the products remained the same. Then the world wide web epoch happened. The availability of Internet connections increased and the ease of navigation and accessibility of information portals via the world-wide web helped shift the black market to an online platform to follow the digitization of goods and information.

Nielsen's Law of Internet Bandwidth is an observation that states the average bandwidth speed will grow by 50% each year. From 1983 to 2014, data suggests this has remained true. Computer systems became more prevalent in households, and because of the ubiquity of always-on broadband systems with speeds increasing at a near-linear rate, Internet connectivity became a supporting element of life itself. Everything shifted with it, not just black markets. Currency, as we mentioned earlier, became a digital thing, as did practically everything else. Music to Movies, financial and transaction information, software to corrupt it all. Everything could be uploaded and downloaded with expedience, and legal or not, everything began to find its way through the series of tubes.

This, of course, led to an explosion in online black market activity. With the increased reliance on computers and the Internet, the market to exploit it grew as well. This began with tools that generally were more precisely targeted – utilities like Back Orifice and Sub7 – intended for sale to users called "script kiddies" (a pejorative term meant to indicate their newbie level in many regards). With the growth of websites built by Internet startups and enthusiasts, closed-source tools were developed and sold to allow script kiddies and beyond to scan, analyze, and attack those websites. Sold for anywhere between $20 to $500 on average (some even for few thousand dollars), these tools generally relied on large swaths of unpatched bugs or vulnerabilities in largely popular software like phpMyAdmin, vBulletin, phpNuke, and other content management systems and administrative panels. In a way, they were similar to modern automated web security scanners -- except rather than searching for both known and unknown vulnerabilities and providing suggestions to fix them, they searched for specific web applicion vulnerabilities and provided utilities to viciously exploit them. Some even granted some time-shared access to botnets like ZeuS to bludgeon websites with unrelenting DDoS or focused Layer-7 attacks, like authentication brute forcing or comment spam. Of course, these tools eventually found themselves on free file sharing platforms like KaZaA and LimeWire, but not before they found plenty of sales on online black markets first.

With all the digitization of information and a black market to follow, however, the financial aspect remained the same, consisting of either cash at a drop point (far less common as time went on) or wired digital currency from one bank account to another. Usually the risk was gambled, and direct account-to-account transfers were done – checking account wire, debit cards, PayPal, MoneyPak cards, et cetera – while other times a questionable escrow may be used. Buyers and sellers were still presented with a possibility of law enforcement detection and seizure. Like those digitized transactions, the web activity itself could also be logged, traced, and archived, even with precautions like encrypted traffic and attempts at anonymizing oneself. But despite the risks involved, thousands of people still took the chance every day.

Why Take the Risk?

Whatever the risk involved, some users of the Internet felt that being told what they can and cannot possess, physical or digital, was akin to oppression. Telling someone they cannot do something is among the easiest ways to inspire them to do it. Human beings are fascinating creatures for a lot of reasons, in particular that for even as logical as we are, we still do some incredibly foolish or backwards things. For example, if you tell a human, "No, you cannot do that, it is not allowed," they will find any conceivable method to do that which they are forbidden to do, even if it is utterly pointless to do so. This is especially apparent in children, but just as much so in adults. Thus, the theory goes, if you tell humans they are not allowed to purchase particular objects, or own certain items in ways they feel they are entitled to, then Hell or high water they will find a way to do it. This is undoubtedly a core reason, if not the core reason behind black markets existing – that rebellious nature inherent to self-awareness – and it remains just as true today as it did in the Assyrian era when black market bazaars first started to exist. Perhaps it could be argued that digital black markets – maybe not all, but some – exist under the belief of free information, free knowledge, and freedom to do with your purchase as you see fit, corporate content makers' controlling wishes be damned.

It all sounds very Robin Hood, like some 21st century "copy from the rich corporations, and give downloads to the poor consumers online" idea, but it also takes a horrifying turn from righteous to indignant and sometimes even downright disgusting with the click of a mouse. Within the ranks of these hackers that felt ethical in their liberation of data, some existed that wanted to profit from burning others. More questionable digital content came into the trade, including malware and virus sales, purchasable vulnerability information and more. With both the copyright industry coming down on the DRM circumvention and copyright infringement groups, and government alphabet soups (FBI, DOJ, SEC, etc.) coming down on the virus trade, these groups began going further underground. They found that to minimize risk, they would need to utilize end-to-end anonymity software, thus fostering a new iteration of digital black markets on a network colloquially termed the "dark web."

These black markets are often hidden, operating on encrypted and anonymized networks such as The Onion Router (TOR). Much like Bitcoin, TOR exists to anonymize data that passes through it. It operates by utilizing a network of anonymous relays that traffic hops through. (Basically, a user connects through an entry node, then their traffic hops through various relays until exiting from an exit node. The traffic from the user's computer and through all nodes including the exit node is encrypted, thereby guaranteeing anonymity – that is, so long as the user's computer does not somehow leak what it is doing and does not connect to an attempted de-anonymizing entry node.) Because of such a deep level of anonymity, the overwhelming majority of TOR traffic is illicit. In fact, over one-third of all TOR traffic consists of dark web black market traffic, including drugs, illicit goods, fraud, and much worse.

The more that illicit or illegal activity was shuttered throughout the normal, everyday dot-com Internet, the perpetrators of such enterprises eventually found their way to alternative, basically lawless outlets for their questionable activity. Initially, it began with communities cropping up on new domains thanks to hosting companies in less policed nations like Russia and Ukraine being welcoming to anything and everything. The advent of cloud computing made it much easier to host illicit or malicious activity, and the hosting country and its policing no longer seemed relevant, with one study putting Amazon AWS as the largest malware distribution host during part of 2013. However, when the owner of TVShack.net found himself facing extradition solely because of the Top-Level Domain (TLD) being .net, many illicit and sinister websites began abandoning their domains in lieu of ccTLDs (Country Code Top-Level Domain), like .it, .cc, and others. (Because .net is a United States TLD, the U.S. government argued extradition was valid since crimes were committed using U.S. property, even though both the owner and hosting itself resided in the United Kingdom.) Then, when even changing TLDs proved ineffective for some organizations (due to increasing large-scale international cooperative and coordinated raids), they began to find a safer home in places accessible via the TOR-network-only .onion TLD. This is because the .onion TLD helps mask the IP address of the server hosting the content, keeping it safe from government raids and host shutdowns. The risk of being discovered or caught was no longer as big a concern as it had been in decades prior.

A Jump Down the Rabbit Hole

The increasing popularity of anonymizing systems and methodologies such as TOR and unlogged VPNs created an underground, hidden environment where nothing was too extreme to host or sell anymore; their world was finally free. These havens of anything-goes became the go-to for anyone wishing to participate in anything with minimal fear of being caught, coming with the unsurprising caveat of often being very seedy, immoral, and even hostile. In one such community, users communicate over the IRC protocol secured and accessible only via the TOR proxy system. The IRC network found itself home to various forms of trolls, including conspiracy theorists, "men's rights activists" (Internet users that argue on behalf of anti-feminism), and others. A large number of the channels (IRC chatrooms) were dedicated specifically to topics users enjoyed trolling, with some users occasionally finding the time to band together and commit "raids" – organized efforts of ruination that typically involved hacking a website, smearing someone's reputation, publicizing confidential or proprietary information, and various other similar activity. Sometimes raids similar to these yielded information dumps not unlike the ones you would see in the news, like Hacking Team and others. A few channels even existed solely for Schadenfreude, so depraved that they gave users a place to enjoy and share nonconsensual pornography and real-life gore. One thing, however, that found itself as a common foundation between these communities, no matter what their focus or amount of trolling, is that they always had a few channels surprisingly active with users happily trading digital and physical goods. All for just a Bitcoin or two.

In wholly unregulated one-on-one sales markets like in this IRC network, reliability proves to be the trait most difficult to find due to the anonymity leading to a lack of liability. Communities like this IRC network deeply valued good reviews of sellers to establish credibility and trustworthiness. Even buyers sometimes had to be vetted depending on the risk to the seller. This is because some of the wares being sold consisted of some of the most illegal and unsavory items one can think of. Some sellers sold physical and tangible goods, ranging from narcotics and marijuana to even guns and explosives. Since Bitcoins provided a way to arrange payment, the physical goods had to be figured out next. This requires an interesting dance – buyer trusting the seller with an address, seller securing packaging to inhibit detection – an interesting dance, but nothing new. Even comedian Mitch Hedberg joked nearly two decades ago that his postal delivery guy was unwittingly a drug dealer – "and he's always on time."

Drug trafficking is an obvious use of any black market. The ubiquity of drug sales, though, afforded the opportunity for those same buyers to see other things of interest that they otherwise normally would not have found. Some sellers in this IRC community specialized only in software utilities, such as ransomware, Trojans, and vulnerability information (e.g. unpatched exploits not yet known to the outside world, WordPress and its plugins being a recently popular category), items they claimed were traded and sold almost as commonly as drugs at times. (In fact, an interesting correlation was made by a couple community members: buyers of viruses and vulnerabilities sometimes also bought drugs from the same place, or at least engaged in discussions thereof. The more complex or expensive a virus or vulnerability they bought, the more complex their experiences and preferences in drugs appeared to be.) The difficulties both buyers and sellers faced were of little consequence, either. In fact, when asked in the IRC network why they took the risk and sold what they sold, some users seemed almost flummoxed, as if they had been asked why they eat food or breathe air. The responses varied, but the mentality seemed almost groupthink among them: It is a free-market right to sell anything people want, and no one has the right to tell people what they cannot buy or sell.

This sort of laissez-faire mentality seemingly permeates a significant amount of the dark web and could perhaps be largely responsible for the popularity of the concept of an Internet black market. One user even suggested that the dark web is perhaps the modern evolution of a decentralized, truly pure democratic libertarian utopia. It became quickly apparent that at least part of the reason for their activities was as some form of protest against centralized government and economy, harkening back to that rebellious nature inherent to self-awareness mentioned earlier. In effect, their activities were simply because they were told they were not allowed to do so, which clashed with their firmly held, almost dogmatic belief in no leadership and no real rules. This was especially apparent in those selling vulnerabilities and drugs. Much less Robin Hood and much more Mikhail Bakunin.

The political and ideological aspect finds itself far more prevalent in the fast-moving pace of chat environments and significantly less strong or abrasive in easier moderated communities such as web forums. In fact, when you make your way out of the anarchistic side of the dark web where the hidden IRC networks lie, the chaotic vibe of the IRC networks mostly disappears and paves way to well organized and cleanly designed websites. These, too, find themselves hidden behind .onion domains accessible only via TOR-enabled web browsers. Everything from the Grams darkweb search engine to various popular wikis (colloquially called The Hidden Wiki, even though it actually consists of a group of unrelated, individual wikis), and more, many looking professionally designed and well-programmed. That is, assuming you know where to find the right 16-character .onion addresses.

Figure 2-TOR Browser (Source: Tor Project)

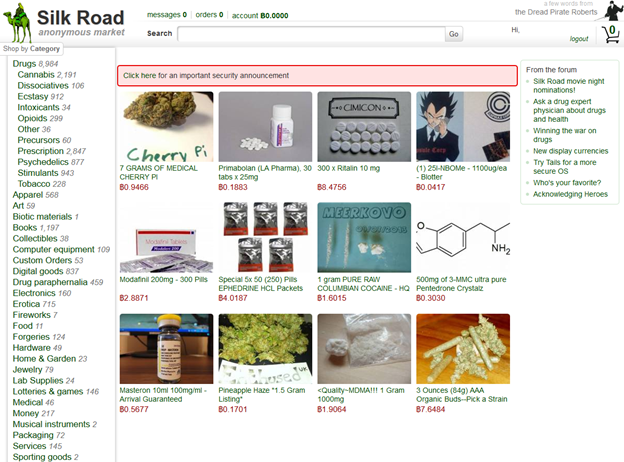

Silk Road – From Han Dynasty to Internet Underground

In around 200 B.C., the Han dynasty of China created what became the most world-renowned and famous network of trade routes of all time, the Silk Road. Fast-forward a couple millennia, and in February 2011 a website bearing the same name opened its doors within the TOR network. Operated by a user named Dread Pirate Roberts (a joke name from the awesome cult-classic movie The Princess Bride), the organization saw itself with slow, but obviously predictable beginnings in illegal drug trade. After just a couple months and a little help from a Gawker article, this new Silk Road organization quickly overtook the historical infamy of its name, establishing itself as the go-to organization for dark web trading, even being dubbed by some journalists as the "dark web Amazon.com". Almost anything imaginable could be bought there, from drugs to software vulnerabilities, even hitmen, apparently.

Figure 3-Screenshot of Silk Road (Source: John Ribeiro, PC World)

In just over two years, Silk Road went from a brand new, relatively unknown black market to one of the biggest illegal trafficking criminal enterprises on the Internet, with one study suggesting upwards of 18% of all American drug users obtained their product through the website. Software vulnerability sales saw an increase during this time, too, as the popularity of a dark web black market provided more opportunity to exchange such information. However, with the increasing popularity of Silk Road came the full focus of the F.B.I. and other law enforcement agencies. Utilizing some tricks to remove the anonymity of Bitcoins, users of the website began finding themselves caught. It was not long until Dread Pirate Roberts – unmasked as Ross Ulbricht – was himself caught, the Silk Road website shut down, and over 144,000 Bitcoins were seized, valued at the time by some estimates at over $28 million USD. But the damage was done, so to speak. The denizens of the dark web learned that a black market can successfully exist on TOR, and that a system can be engineered to establish reliability, trust, and credibility between buyers, sellers, and the organization that hosts their transactions.

The joint task force raid on Silk Road was not effective for long, resulting in fracturing the central nature of Silk Road into dozens of smaller, more difficult to trace entities that rapidly grew to take its place. Shortly after the first was shut down, a replacement was swiftly brought online, fittingly titled Silk Road 2.0. That, too, found itself shuttered by a massive, coordinated international raid – Operation Onymous – exactly one year to the day that it opened, taking with it organizations and hidden servers of over 400 other TOR-anonymized .onion domains. Blue Sky, Cloud Nine, Hydra, Pandora, and over 50 other similar black markets were shuttered. But with each raid came more publicized information about how the proprietors of these websites got caught, and with each iteration the next generation of hosts learned how better to hide themselves. Silk Road 2.0 and over 50 other black market organizations fell during Operation Onymous, but more like Agora and Evolution took their place. Less than a year later, Evolution abruptly disappeared, its administrators absconding with over $12 million USD in escrow, but Agora and a few others remain. One of the markets that got shut down – Hydra – had an ironically fitting name for the whole process: cut off one head and two more grow back in its place. (The IRC network mentioned earlier has since disappeared during the writing of this article, reportedly being shut down or seized during a recent multi-organizational raid similar to Operation Onymous.)

With each raid and shutdown, the dark web black market fractured further and further into smaller pieces. This has proven effective in keeping the organizations more hidden from law enforcement attention by divvying up the target on their back. Rather than one giant target in the form of a single entity, segment the community into smaller, more specialized organizations. This fracturing posed an additional problem to law enforcement: not only were the replacements getting better at hiding, but the battle itself made for great media. Attempts to shutter these organizations created a Streisand Effect, bringing more attention to the very thing the government was trying to shut down. News of each raid brought more publicity, and social media spotlights were shined on the dark web itself. Huffington Post, Gawker, shared on Facebook and Twitter, Reddit threads and new sub-Reddit boards dedicated to the subject – news and social media began spreading the stories like wildfire. Each retweet and like led more common, less tech-savvy users to discover the concept of a dark web and its black markets, and people began to flock to them. The larger markets fell, but more single-business websites spawned to meet demand and sell specific items: some for drugs, a few for guns, and many new, user-friendly ones for the blooming digital 'warez' market.

The Warez of the Darkweb

Two things dominate the dark web black market today: drugs, of course, and financial fraud, like stolen credit card numbers or personal financial information. The former only needed the existence of two systems to flourish explosively in the way that it did – an anonymous cryptocurrency, and an anonymizing proxy system. Financial fraud, however, needed these and one more variable in the mix to complete its trifecta: a way to continue scraping financial information to defraud. While malware trading was nothing new, a whole new generation of black market warez gained focus during the Silk Road era. Unlike the anti-DRM circumvention mentality, these buyers and sellers sought not free information for the benefit of others, but proprietary information solely to profit off the harm of others. Cheap, easy money by exploiting vulnerable computers – that was the sales pitch, and it has been largely successful.

For the longest time, fraud has been done via emails containing either infected attachments or information directing a victim to perform some action. (Seriously, when is that Nigerian prince going to wire us our millions?) Viruses and trojans have existed since about as long as computers have been networked together, usually developed by ambiguous, anonymous people or teams for their own isolated purposes. Generally, it was the data these groups mined that found its way onto digital black markets in each of their iterations, and not the software to procure the data itself. This business model remained relatively stable for decades, a few savvy developers writing the viruses, keeping it to themselves and profiting off the fruits of their labor. The credit card numbers gathered, not the method to gather them, were the product, and sales were good. Eventually, though, some began exploring selling the utilities themselves, and not just the viruses but also components thereof. The billion dollar industry of financial fraud was growing, evolution had to happen in order to support this growth, thus taking the middle-man out was the next logical step.

Components of malware, even complete kits, began being sold on these markets in specialized, customizable form, sometimes even as licensable software development kits (the irony of licensing black-market software is pretty amusing). The growth of software development being a cool, trendy thing – be it in Go, HTML5, jQuery, ArnoldC – led to a more pwn-it-yourself DIY attitude. Vulnerability descriptions, example and explanation code, even complete software packages that just needed some Makefile customization tweaks and a recompile became increasingly popular items of trade. Specifically, vulnerabilities known as 0day exploits – named because, upon discovery, the victim software's developers and white-hat security researchers have zero days to learn how to correct it – quickly grew as commonly sold items in this particular enterprise. The reason is quite simple, really: most vulnerabilities that are exploited are "open source," or already known to the public. A 0day, however, is proprietary, granting the buyer exclusive rights to exploit it and profit the most from it. These can come in multiple forms – exclusive sale of a vulnerability (this is an example of where buyer reliability and trustworthiness becomes an important factor), a sort of software development kit, or even boutique customizable kits ready for deployment, no compiler necessary.

A sort of interesting bell curve has happened with black market software exploit sales. First, it started closed-source, with just the end result being sold (credit card numbers, financial history, etc.). Then, it grew into a sort of trend to DIY your own, based on closely-guarded secrets (unpublicized 0day vulnerabilities, for example). But now, with the Average Joe being the normal browsing customer of these black market shopping carts, the curve is returning back to closed source. The DIY trend is still satiated, but boutique kits now grant a level of simplicity harkening back to an era of script kiddie easiness, requiring nothing more than a working knowledge of Bitcoin and TOR. Turnkey web scanner and exploitation kits, botnet time-sharing, and malware generators are nothing new; the ability to sell your warez easily because no one has to run gcc is obvious. Nowadays, 0days in Windows, for example, are frequently exploited for either zombie malware or ransomware – a virus that encrypts your personal data and requires you pay a ransom within a few days, or the key to unlock your data gets destroyed and you lose it forever.

Sometimes these utilities are sold as "white-hat" penetration testers or scanners, but in reality they are $250 exploit toolkits purpose-built for annoyance. More complex systems come with a significantly higher price, but also a greater yield – a $4,000 USD investment grants you access to potentially hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions in profits (the five hackers behind the ZeuS toolkit bank account hack in 2010 successfully stole over $70 million). All these, unfortunately, require you to get your hands dirty a good bit, though, and also require some fair amount of technical expertise. This gave rise to point-and-click 0day exploit websites that handle everything for you, being about as simple as signing up for a social media account. Systems like Tox let you do everything over TOR, use Bitcoin to receive payment (they, of course, take their 20% off the top automatically), and task you only with getting your boutique ransomware out there. Just sign up anonymously and for free, create your malware, spread it, and wait for the Bitcoins. How simple is that?

These warez have yielded incredible success, too. Through both exploiting known, publicized vulnerabilities, as well as procuring 0day information and software, then combining the two, hackers part of the "Carbanak cybergang" managed to steal tens of millions of dollars through an absurdly successful data manipulation attack. Ironically, supporters of cryptocurrency would claim this kind of attack is one of the main reasons for the existence of non-federated cryptocurrency: the hackers were able to make the banking systems think an account had an arbitrarily higher amount than it actually had by simply editing the balance, thereby allowing the withdrawal of magically generated money. A series of successfully exploited 0days, some potentially exchanged via black market sales or trades, let the Carbanak group make ATMs freely give them $7.3 million. The cybercrime industry itself is incredibly lucrative, costing over $114 billion USD every year, with an increase of 78% in just four years. The profits black-hat hackers yield from this is sometimes more difficult to measure, but it, too, still measures in the tens of billions annually.

Windows 0days are not the only area seeing boutique point-and-click generator websites like Tox. TOR-hidden website interfaces exist for many kinds of digital attacks, the profit aspect (for the attacker) often not even being an important component. The script kiddie ideology of "doing it for the lulz" (doing something because it amuses the perpetrator) finds itself incredibly satiated in these boutique markets. For fractions of a BTC ($10-$50 USD on average), a user can anonymously request a segment of a botnet, such as ZeuS, perform some attack against a website, with no intentions other than to annoy and disrupt the victim. No longer does an attacker need to run a script on his or her computer, or compile any software, or connect to a secret IRC network, or do practically anything. In fact, the attacker need not even have much of any technical prowess – just a basic, high-level, abstract understanding of web attacks. Simply install TOR, find the right .onion website, pay a little BTC, choose your target and attack (DDoS and email spam, of course, being the most common), and click a button. The guides and tutorials are so well documented that a Baby Boomer who has difficulty using their printer could reasonably perform these attacks.

What Can Be Done For Protection?

The quick answer is also the most uncomfortable one: not a whole lot actually can be done. Government agencies know of these black markets and are working quickly to shutter them. White-hat researchers and major software development firms like Oracle and Adobe are trying to procure covertly, even buy 0day vulnerability information in order to race toward fixes faster than the vulnerabilities can be exploited on a large scale. Only so much can be done, however. In May this year, the IRS declared over 10,000 tax accounts were compromised due to hackers having incredibly detailed information about taxpayers (like address history, credit report data, employment records and more). Data breaches like this are not the result of a 0day on IRS.gov itself, but from the slow and steady progression of vulnerabilities being exploited over time against various organizations, or even from the large-scale spread of data logging aggregation malware.

Protecting against this is as complex as asking, "How do we end poverty?" For an end-user, good security practices are a major first step. Good anti-virus and anti-malware software, like the free products from AVG or Malwarebytes, are crucial. Not opening untrusted email attachments and careful web browsing habits such as SSL-connectivity verification, validation of website authenticity and reliability, and browser protection add-ons are all just as crucial, as well. These steps alone can prevent an extremely large amount of potential fraud, as the overwhelming majority of email spam and DDoS attacks are sent from compromised desktop computers.

Content providers, especially those with eCommerce online shopping carts and other personally identifiable information, have perhaps an even more complex duty. Good development standards, such as following a Security Development Lifecycle (actively auditing and securing code during development), keeping systems and services updated with security patches, and maintaining a strong security posture within a network's entire infrastructure (strict adherence to good practices, auditing, reporting, incident management and more) all will help lessen the probability of falling victim to vulnerabilities, especially 0days. Unknown vulnerabilities still pose a risk, but a good web security scanner can help reduce these. While specific 0days may be unknown to a web scanner, they still have the ability to discover them and even provide advisories long before the impacted software is patched. Discovering vulnerabilities and potential 0days prevent the probability of further intrusion and cascade effects. (Almost all recent major security breaches required at least two different vulnerabilities to be exploited.) Were one of these vulnerabilities patched or protected against, things could have ended with far less fallout, both customer and financial, for the victims of those attacks.