Clickjacking Attack on Facebook: How a Tiny Attribute Can Save the Corporation

This article explains the origins of the Clickjacking Attack and how it works. It then examines how a researcher discovered a Clickjacking bug on Facebook and how Facebook responded to the Clickjacking attack. Finally, the article provides advice on how to prevent Clickjacking Attacks by using the X-Frame-Options HTTP security header.

The clickjacking attack introduced in 2002 is a UI Redressing attack in which a web page loads another webpage in a low opacity iframe, and cause changes of state when the user unknowingly clicks on the buttons of the webpage. In this article, we explain how the Clickjacking attack works and the importance of the X-Frame-Options header, including a discussion of a recent discovery by a researcher who found a Clickjacking attack on Facebook.

Introduction to Clickjacking

This type of attack was ignored until 2008, when the inventors of the attack, Jeremiah Grossman and Robert Hansen, acquired authorization on a victim’s computer through Adobe Flash by using a Clickjacking attack. Grossman originally named this attack by combining the words 'click' and 'hijacking'. The name 'Clickjacking' passed through different categorizations and name changes since. For example, the attack in which an attacker collected likes for his own post using the Clickjacking method was later known as 'LikeHijacking'.Although the Clickjacking attack has been prevented with methods such as Frame Busting, the most effective defense against these attacks was introduced by Microsoft in 2009. With the release of Internet Explorer 8, Microsoft released the X-Frame-Options (XFO) HTTP response header. Right after the announcement all major browsers implemented this header, and in 2013 RFC 7034 was released.

How Does the Clickjacking Attack Work?

The Clickjacking attack method works by loading the target website inside a low opacity iframe and overlaying it with an innocuous looking button or link. This then tricks the user into interacting with the vulnerable website beneath by forcing the user to click the apparently safe UI element, triggering a set of actions on the embedded, vulnerable website.

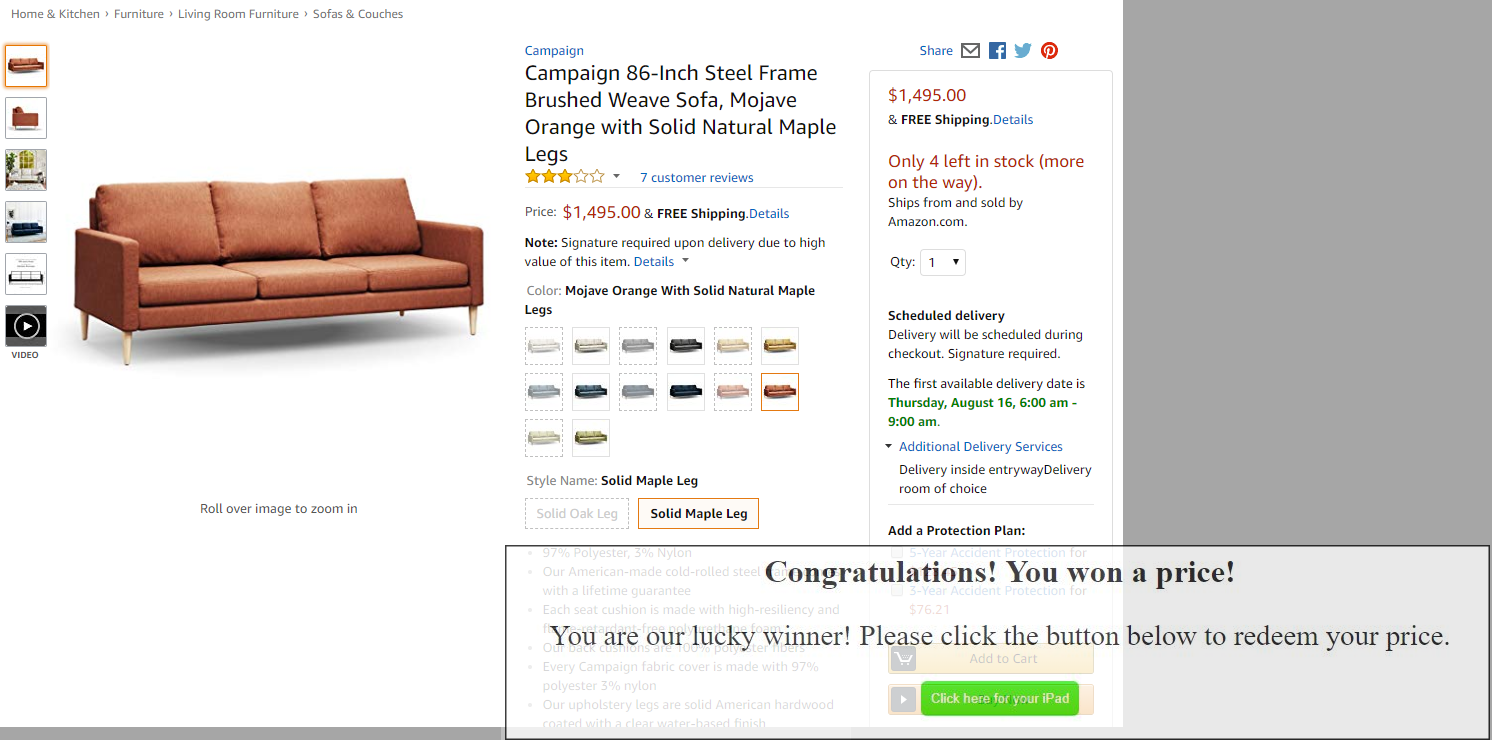

In this example, Amazon is loaded in a low opacity iframe and is therefore not visible by the user. The user sees the Click Here button. Once they click on it, however, only the Buy button on Amazon is actually clicked, triggering a set of actions on Amazon. (Please note, that Amazon is not vulnerable to clickjacking, and this is merely an example of how it would work.)Since these interactions take place as if the victim was intentionally browsing the website, the interaction triggered on Amazon will also include the victim’s credentials (such as Cookies).

The Clickjacking Bug on Facebook

On December 21, a security researcher reported his investigation where he saw suspicious posts shared on his friends’ Facebook walls and uncovered a scam campaign. When he clicked on a link that directed him to a comics website, he was asked to confirm his age. After confirming his age, he was redirected to the comics website, but the post was also published on his Facebook wall without any action on his part.The researcher discovered an iframe and acquired the source code. He found out that these frames ended up on this Facebook URL:https://mobile.facebook.com/v2.6/dialog/share?app_id=283197842324324&href=https://example.com&in_iframe=1&locale=en_US&mobile_iframe=1When you click on this link, you’re prompted to share the content on your wall.What’s interesting is that the researcher realized that the XFO header was set properly on the page. That would normally stop any iframes (even Facebook pages) loading on the page:X-Frame-Options: DENYThe researcher proceeded to check whether the X-Frame-Options header was implemented correctly on all major browsers. He confirmed that they all worked as expected. Next, he checked whether the built-in browser in Facebook’s Android app implemented the XFO header correctly. It turned out that the XFO response header was not set when the user logged in to Facebook from a mobile device.

How Did Facebook Respond to the Clickjacking Attack?

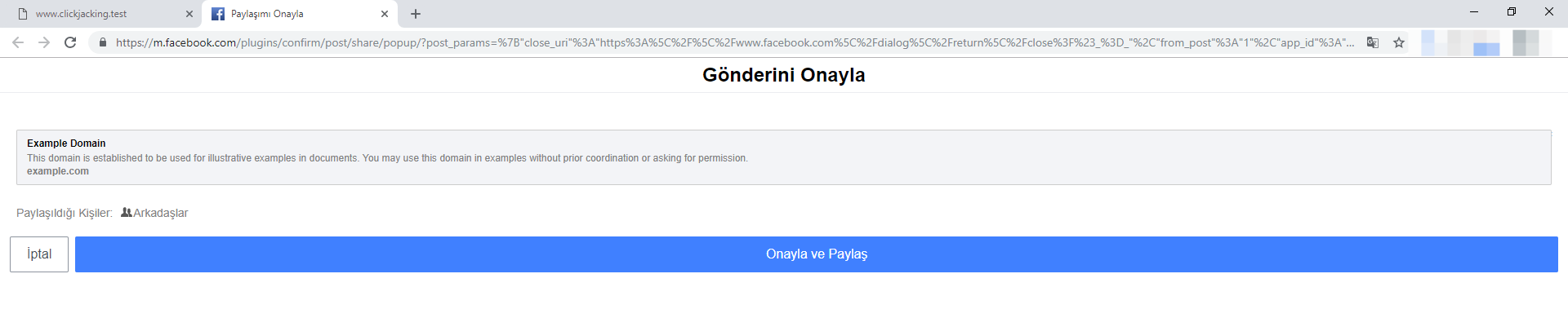

Facebook refused to fix this issue, but as a precaution, it created a second prompt page to give users control over whether they wanted to proceed with the share.

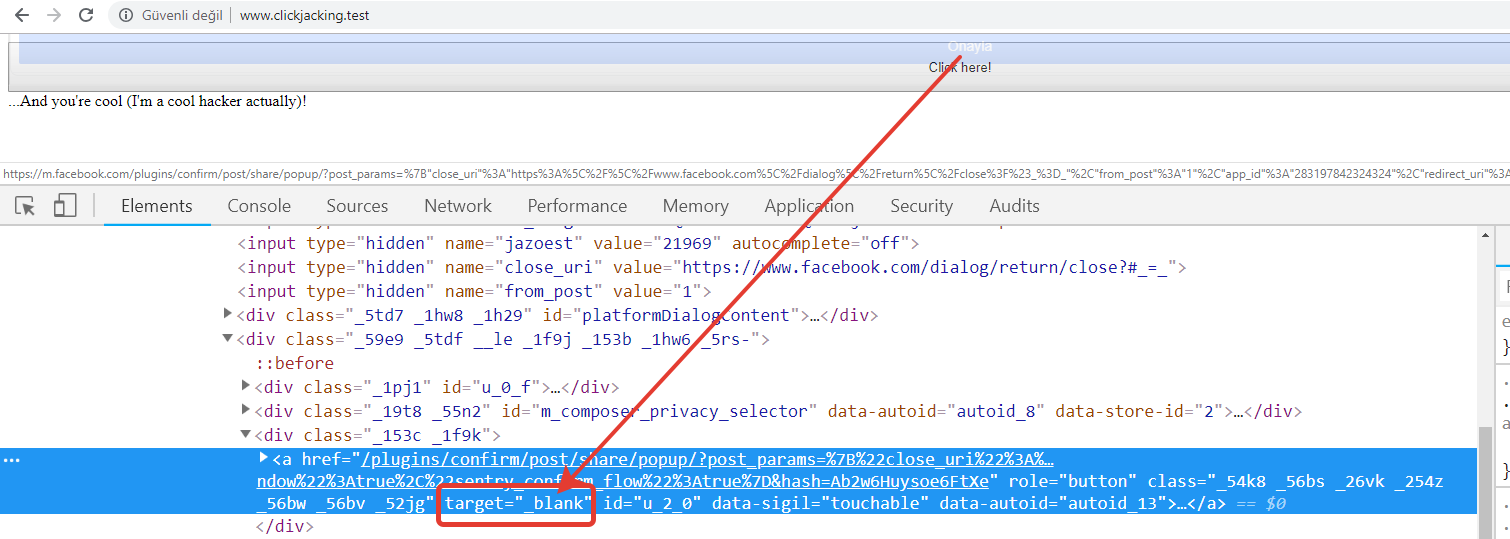

So, how does Facebook's fix work? Whenever you click the button to share the post, the second confirmation page opens in a new tab. It asks you whether you want to share the message and lets you choose the people you want to share the link with. The new page opens due to the “_blank” value added to the target attribute in the href element on the first page. Whenever it is set, the linked page behind the link is opened in a new tab. This results in a thwarted clickjacking attack. This is because, the new tab correctly implements the X-Frame-Options: DENY feature.It's hard to say why Facebook decided to open a completely new tab to share a message. This makes sharing just a tiny bit more inconvenient. For a company like Facebook, that aims to make sharing content as effortless as possible, this sounds like a terrible fix. I wouldn't be surprised if this was only a temporary solution or if Facebook actually used this second page as extra advertising space.

How to Properly Prevent Clickjacking Attacks in Your Web Applications

In order to protect users from UI Redressing attacks like Clickjacking, the best tactic is to prevent malicious websites from framing pages to render with iframes or frames. The most effective method is by using the X-Frame-Options HTTP security header.

X-Frame Options Directives

There are three X-Frame-Options directives available.X-Frame-Options: DENY | SAMEORIGIN | ALLOW-FROM URLDirectiveDescriptionDENY:The page must not be embedded into another page within an iframe or any similar HTML element.SAMEORIGIN:The website can only be embedded in a site that’s paired in terms of scheme, hostname and port. For example, https://www.example.com can only be loaded through https://www.example.com, while https://www.attacker.com, and even http://example.com, are not allowed to embed it.For further information about Same-Origin Policy, see Introducing the Same-Origin Policy Whitepaper.ALLOW-FROM URL:The website can only be framed by the URL specified or whitelisted here.There are two important points to remember with X-Frame-Options:

- Chromium based browsers only partially support X-Frame-Options (the ALLOW-FROM directive is unavailable)

- Using the ALLOW-FROM URL instruction, we can whitelist only one domain and allow our website to be loaded in an iframe.

Important Points About the X-Frame-Options HTTP Header

- The X-Frame-Options header must be present in the HTTP responses of all pages

- Instead of X-Frame-Options, the Content-Security-Policy frame-ancestors directive can be used:

Content-Security-Policy: frame-ancestors 'none'; // No URL can load the page in an iframe.Content-Security-Policy: frame-ancestors 'self'; // Serves the same function as the SAMEORIGIN parameter.Content-Security-Policy: frame-ancestors https://www.example.com;

This serves the same function as the ALLOW-FROM instruction. The most important thing is that you can whitelist more than one URL by using this instruction.

Content-Security-Policy: frame-ancestors https://www.example.com https://another.example.com;