Brave Browser Sacrifices Security

Brave is a browser that blocks ads and website tracking to improve user privacy and security. This blog post describes a controversial update to Brave that contained a whitelist of tracking URLs, causing online discussions, and a temporary but active solution. This blog examines some key terms and suggests how Brave could learn from Firefox.

Brave is a new, free an open-source web browser with a built-in adblocker. It was developed by a team led by Brendan Eich, inventor of JavaScript and a former Mozilla Foundation employee.

The Brave browser uses the motto, ‘You are not a product’. It focuses on improving the privacy and security of its users. Brave also brings a new approach to the advertisement ecosystem by ensuring that both advertisers and users benefit from advertisements by decreasing the amount of disturbing ad content. Advertisers are introduced to a more relevant user range, while users are offered the opportunity to convert their ad experience into an income source.

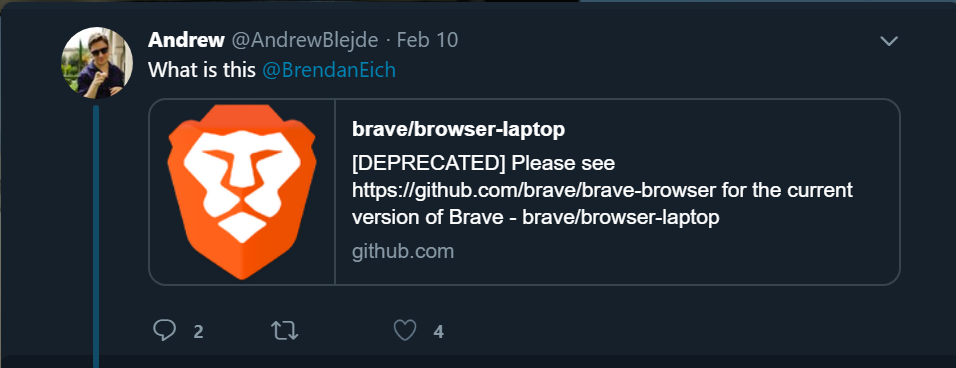

This article is not a customer review. It is an analysis of the browser’s security, sparked by a Twitter discussion on February 10 of this year.

What Makes the Brave Browser Different (And More Secure)?

The Brave browser blocks all third party requests and cookies by default, without the need of extensions. It does so to prevent users from being tracked online. Its developers claim that it is eight times faster than Google Chrome and Safari, and that it represents a concept and project that is far bigger than merely that of a browser.

Brave Browser’s ‘Hidden’ Whitelist of Tracking URLs

A Twitter user tweeted and tagged Brendan Eich, CEO of Brave Software, asking what the new update on the browser’s repo meant in terms of the security aspect of Brave.

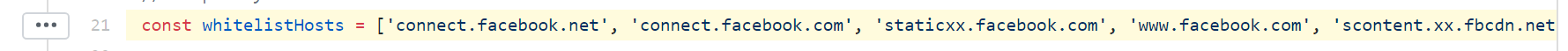

This question was raised because around three years ago, code was added to the browser’s Github repo to whitelist certain third party domains. The Facebook URLs that are used to track users were included in this whitelist.

This caused a huge disappointment among users because Brave was supposedly a secure browser, focused on user privacy. In fact, security and user privacy are part of their marketing strategy. Eich replied to the tweet, saying that they prepared the whitelist in response to user requests. Without loading the third party scripts and styles, the features like Facebook Connect and Facebook Share on the webpages do not work as expected.

Eich had a point. When you disable the third party components, certain functions that depend on the libraries within these components will not work properly on the websites you visit.

However, before the controversial update, despite these limits on the Brave browser, Google’s functions worked well. This was because the functions didn’t force the scripts to be loaded within the page. They instead open a new window after the user interaction and proceeded from there.

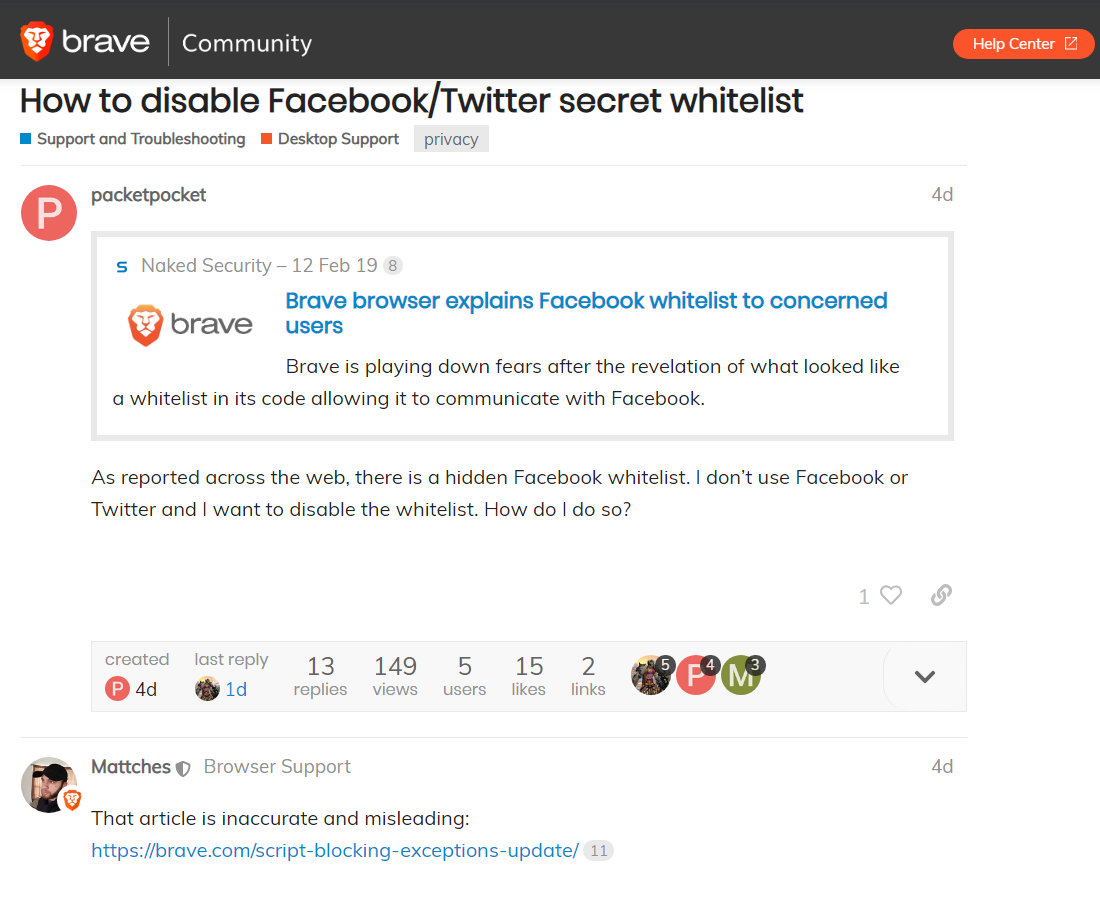

Brave Browser Team’s Response to the Whitelist

In response to the ensuing Twitterstorm, Brave released a public announcement – Script Blocking Expectations Update – while the complaints and discussions continued. In this announcement, Brave disclosed that with this update, script loading isn’t banned but tracking will be blocked as it always had been. The developers stated that during script loadings, the script cannot set any cookies or access the cookies that are already set on the browser. Without them, it’s not possible for the user to be tracked, since fingerprinting isn’t an effective way of tracking users.

Since the whitelisting process is hardcoded, users who didn’t have an account on Facebook and Twitter started to look for ways to disable this feature.

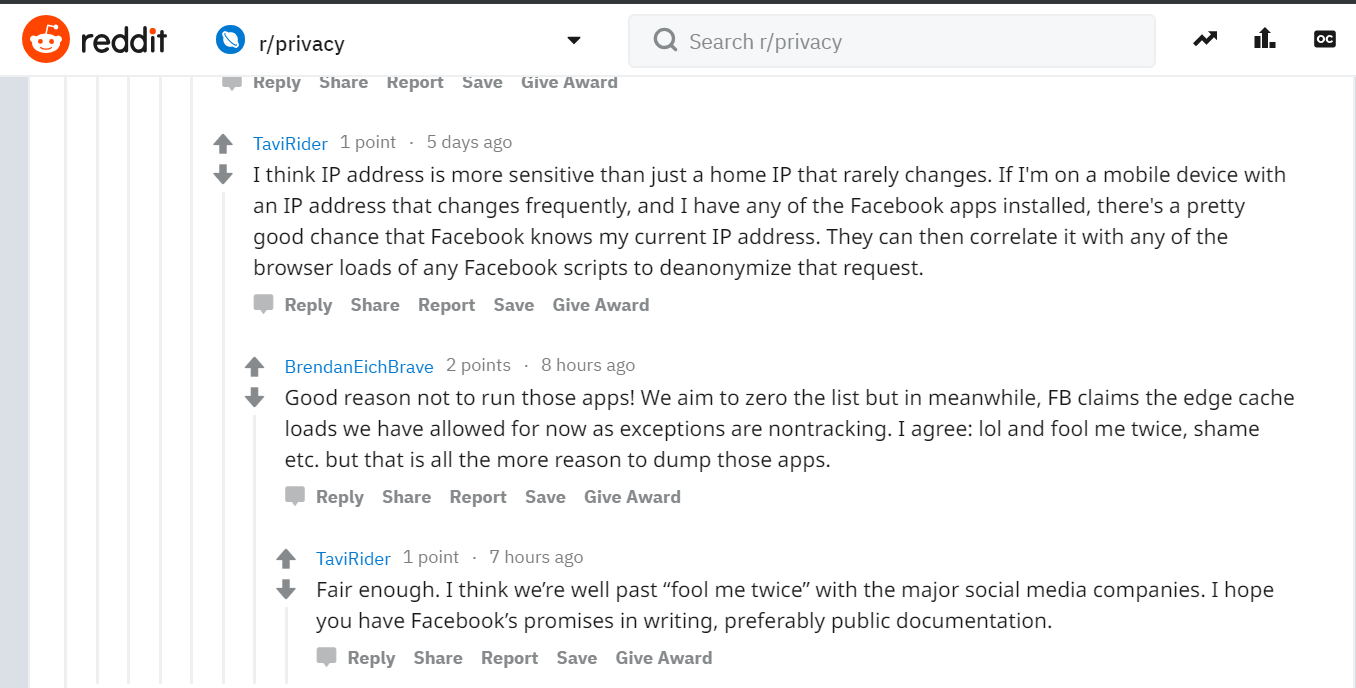

Although Brendan stated that fingerprinting wasn’t an effective way of tracking users, connections made from mobile devices over cellular data could easily be singled out using this method. So it still caused doubts (see Reddit).

Temporary But Active Solution for the Whitelist of Tracking URLs

According to this comment on top of the code block on the updated repo, the mechanism is only temporary.

// Temporary whitelist until we find a better solution

However, since 2016 there have been no updates to the code, while there are new additions to the whitelisted URLs. The latest additional URL is from Twitter: cdn.syndication.twimg.com.

The Difference Between First Party and Third Party

Throughout Brave’s announcement and discussions within the community, jargon has developed to enhance the depth of the matter. Let's clarify two phrases.

- First Party refers to the website you access directly by entering the address into your web browser (e.g. www.example.com). All the resources loaded within this domain to allow the website to function properly belong to the First Party concept.

- Third Party refers to all origins that are deliberately or mistakenly requested from the website you visit.

How Should The Brave Browser Team Have Addressed The Tracking URLs Whitelist Issue?

Brave could have implemented settings which allow users to choose their own privacy options and levels. For example, Firefox lists a variety of options when it comes to third party services.

This was one of the methods suggested in the community discussions.

These are the security features that Firefox has but Brave doesn’t:

- Firefox relies on its own certificate trust chain instead of that of the operating system.

- Firefox doesn’t use the operating system’s proxy settings. Instead, proxy settings must be configured on the browser.

Conclusion

While users generally don't expect much privacy from browsers like Google Chrome, the Brave browser promised to do better. By whitelisting the domains of some of the biggest data collectors on the internet, they have lost the trust of a large number of users and will need to work hard to get it back. An editable whitelist, like the one Firefox offers, would have solved the technical problem faced by users who wanted to use Facebook Connect or Facebook Share, without having to hardcode the domains. Only time will tell whether Brave will improve in the future and offer the golden promise – a truly untracked browsing experience.